Biography: Harry H. Jones

A True Renaissance Man: Attorney Harry H. Jones

By Sean Duffy

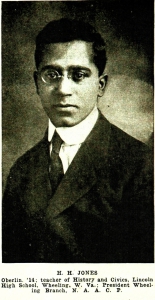

Harry H. Jones was a true Renaissance man. Born November 7, 1887 in Wheeling, he graduated of Lincoln School and Lincoln High School, then Oberlin College in 1914. [1]

Harry H. Jones was a true Renaissance man. Born November 7, 1887 in Wheeling, he graduated of Lincoln School and Lincoln High School, then Oberlin College in 1914. [1]

He became a teacher of history and civics at Lincoln School, earning the nickname “professor” before completing his law degree at Howard University in 1929.

Jones married Edith Walker Redman on Dec. 10, 1942. [2]

Mr. Jones was editor of a Wheeling African American newspaper known as The Advocate until resigning in September 1923. “While [Jones was] on the staff,” The Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “[he] made the paper felt with his strong dissertations regarding race questions in the community.” [3] Indeed, his writing reveals an eloquent spokesman regarding such issues.

Jones wrote, for example, for the Wheeling Majority, a popular socialist newspaper during Wheeling’s union heyday, for whom he crafted an insightful and prescient article about the 1919, post WWI race riots and how the experience of the European war opened the consciousness of America’s black soldiers, a view that has become widely accepted. [4] Jones, then a 32 year old teacher at Lincoln School, wrote in part:

“…the development of race consciousness among Negroes during the war has tended to spur their demands for consideration at the hands of their fellow Americans. Prior to the war the Negro was wont to confine his agitation for justice to restricted channels on this side of the Atlantic. Today, following the example of other oppressed peoples, he is carrying on an international propaganda. Formerly, when he was attacked by mobs, he ran; today he stands and defends himself. He is conscious of having rendered efficient service to his government during the war, and now he asks that his government reward him with the rights and privileges of American citizenship. The war broadened his views. It brought him in contact with many races of mankind. Either on the battlefield or through the press, he found that France was willing to accept him at his worth. He has faced death many times more horrible than a Georgia mob could inflict on him. He has lost the fear of death…the civilian Negro, having given his best in manhood, means and brawn to ‘make the world safe for democracy,” having had sounded repeatedly in his own ears that all mankind is entitled to self-determination, has formed the opinion that Democracy ought to begin at home, and that he ought to share in the fruits of victory. He cannot appreciate our championing the right of weak people in Europe and Asia to self determination and our remaining silent on his right to enjoy it at home.” [5]

Jones also wrote for The Pittsburgh Courier, a nationally respected black newspaper, and for the The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois himself, for whom he wrote articles under the title, The Negro Before the Courts. [6]

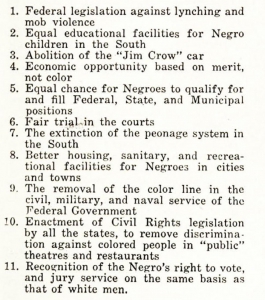

Jones’s list of issues well covered by the center of black leadership in 1920 appeared in The Crisis magazine in March of that year. In March 1920, Jones contributed a rather important article to The Crisis, titled, “The Crisis in Negro Leadership,” in which he discusses the visions of the right (Booker T. Washington), center, and new left or radical wings of that leadership. Building upon his thesis from the 1919 article about black soldiers, Jones dismissed the conservatives as having surrendered to the white South, and eschewed the socialist left out of a fear of alienation from “fair-minded whites” and reprisal by “white workers.” Concluding that the middle ground was the best path forward, Jones wrote:

In March 1920, Jones contributed a rather important article to The Crisis, titled, “The Crisis in Negro Leadership,” in which he discusses the visions of the right (Booker T. Washington), center, and new left or radical wings of that leadership. Building upon his thesis from the 1919 article about black soldiers, Jones dismissed the conservatives as having surrendered to the white South, and eschewed the socialist left out of a fear of alienation from “fair-minded whites” and reprisal by “white workers.” Concluding that the middle ground was the best path forward, Jones wrote:

“The majority of intelligent and active Negroes belong to this [center] class. Its methods call for agitation, education, legislation, and law enforcement. It has a definite program … The Centre has these points in its favor: the spirit of equality running through American legislation; the capacity of the nation to respond to high ideals in national crises; the active support of many high-minded whites in their fight to secure justice for the Negro … It has fought against moving picture plays that fostered race feeling; it has carried on strong propaganda against lynching and mob violence … The two races must find a common ground to work out their differences in a friendly fashion and in mutual good will. Shall they work according to American customs, standards, and traditions? Or shall they follow European State Socialism? To every Negro who prizes his racial inheritance and believes in its possibilities, I suggest in all candor that he think seriously upon which wing he will follow, for upon his choice will hinge the future of his race and, perhaps, the nation’s.” [7]

As President of the Wheeling branch of the NAACP in 1919, Jones praised West Virginia Governor Cornwell for the latter’s stand against a “double lynching” in Huntington and in support of federal the anti-lynching Curtis and Dyer bills, which were never not passed. [8]

Jones served as the West Virginia field supervisor of the “Civilian Defense for Negro Activities, held the federal position of Clerk, Office of Recorders of Deeds, Wheeling, and was a member of both the Wheeling Zoning Commission and the West Virginia Human Rights Commission. [9]

Jones served as the West Virginia field supervisor of the “Civilian Defense for Negro Activities, held the federal position of Clerk, Office of Recorders of Deeds, Wheeling, and was a member of both the Wheeling Zoning Commission and the West Virginia Human Rights Commission. [9]

In 1936 he delivered a speech titled “Wheeling’s Twentieth Man,” on WWVA Radio, a very important document about black life in Wheeling in the Jim Crow era.

Explore the Civic Empathy Through History Project based on the 20th Man Speech.

Harry H. Jones wrote a column titled, "Along the Color Line," which ran in the Wheeling Sunday News-Register from Feb. 1946 to Jan. 1948.

Harry H. Jones wrote a column titled, "Along the Color Line," which ran in the Wheeling Sunday News-Register from Feb. 1946 to Jan. 1948.

(Compiled by Chuck Julian).

Read the Column

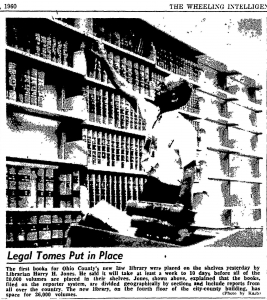

In 1960, he was appointed Librarian of the Ohio County Law Library, remaining in that position until his retirement in 1971. [10] Jones was not the first black law librarian in Ohio County. That distinction belongs to Elijah J. Graham, Jr., who was named to the position in 1917. [11]

Harry H. Jones died in 1974 at the age of 87 and is buried at Greenwood Cemetery. [12]

End Notes

[1] Wheeling Intelligencer, Thursday, November 21st, 1974, p. 20.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Pittsburgh Courier, Sept. 15, 1923, p. 13.

[4] See for example: Bryan, J. “Fighting for Respect: African-American Soldiers in WWI.” armyhistory.org. Accessed Feb. 20, 2121. See also: Barbeau, A. The Unknown Soldiers: African-American Troops in WWI. 1996.

[5] The Crisis. Vol. 18. 1919. p. 304.

[6] The Crisis. Vol. 4. 1933. p. 173.

[7] The Crisis. Vol. 19. 1920. p. 256.

[8] Wheeling Intelligencer, Thursday, Dec. 18, 1919. p. 2.

[9] Wheeling Intelligencer, Thursday, November 21st, 1974, p. 20.

[10] Wheeling Intelligencer, Saturday, July 23rd, 19. p. 3.

[11] The Crisis. April 1917. p. 300.

[12] Wheeling Intelligencer, Thursday, November 21st, 1974, p. 20.