Rebecca Harding Davis

Author, pioneer in literary realism

— from Wheeling Hall of Fame (Inducted in 1984)

Rebecca Harding Davis was a pioneer in literary realism.

In 1861, when her story, "Life in the Iron Mills," was published anonymously in The Atlantic Monthly, few people in Wheeling could have imagined that this novella about human tragedy had been written by their 30-year-old spinster neighbor, Rebecca Harding.

Born in Washington, Pa., in 1831, she had lived in Wheeling from the age of five. Her English-born father, Richard, was an insurance executive and also city treasurer for 14 years.

As a teen-ager, she attended Washington Female Seminary, where she was graduated valedictorian in 1848. There was nothing in her upbringing to suggest she would be able to picture so vividly the grim life of immigrant industrial workers and their harsh working conditions.

However, she was obviously influenced by the change in Wheeling from an idyllic Virginia village to a smoke-filled milltown.

The Civil War created an even more dramatic change in Wheeling and in subsequent work, no longer anonymous, she told of the "general wretchedness, the squalid misery, which entered into every individual life." She described the savagery of war and her talent drew the admiration of the New England writers Emerson, Holmes, Alcott and her favorite, Nathaniel Hawthorne — all of whom she met while traveling with her brother to Boston.

She also caught the attention of Philadelphia lawyer L. Clarke Davis. They struck up a correspondence, soon met and were engaged. They were married in St. Matthew's Episcopal Church in Wheeling during a March snowstorm in '63 and took up residence in Philadelphia.

Rebecca Harding Davis wrote "Waiting for the Verdict," which laid bare social hypocrisy and racism. Her novel, John Anderson published in 1874, was based on political corruption. Ever in the vanguard for human rights, she authored "Put Out of the Way," exposing mental institutions, and she and her husband helped reform Pennsylvania laws regarding treatment of the insane.

She became a contributor to Harper's and Scribner's and an associate editor of the New York Tribune. In the last decade of her life, she wrote children's stories, reflecting her continued concern with moral uplift.

She gave birth to three children, and one of them Richard Harding Davis, became the most celebrated journalist of his era. On his mother's seventieth birthday, he wrote in tribute, "From the day you struck the first blow for labor in 'The Iron Mills,' on to the editorials . . . with all the good the novels, the stories brought to people, you were always making the ways straighter, lifting up people, making them happier and better. No woman ever did better for her time than you and no shrieking suffragette will ever understand the influence you wielded, greater than hundreds of thousands of women's votes."

After her husband's death in 1904, she spent much of her time at Richard's estate at Mt. Kisco, N. Y. She died on September 29, 1910.

➤ View Rebecca Harding Davis books available to check out from the Library

➤ View books about Rebecca Harding Davis available to check out from the Library

➤ Download Life in the Iron Mills through WVDeli with your OCPL library card

➤ Download Life in the Iron Mills through Hoopla with your OCPL library card

General William Wirt Colby: a story by Rebecca Hardy Davis

Adventures in Archives: The Harding House

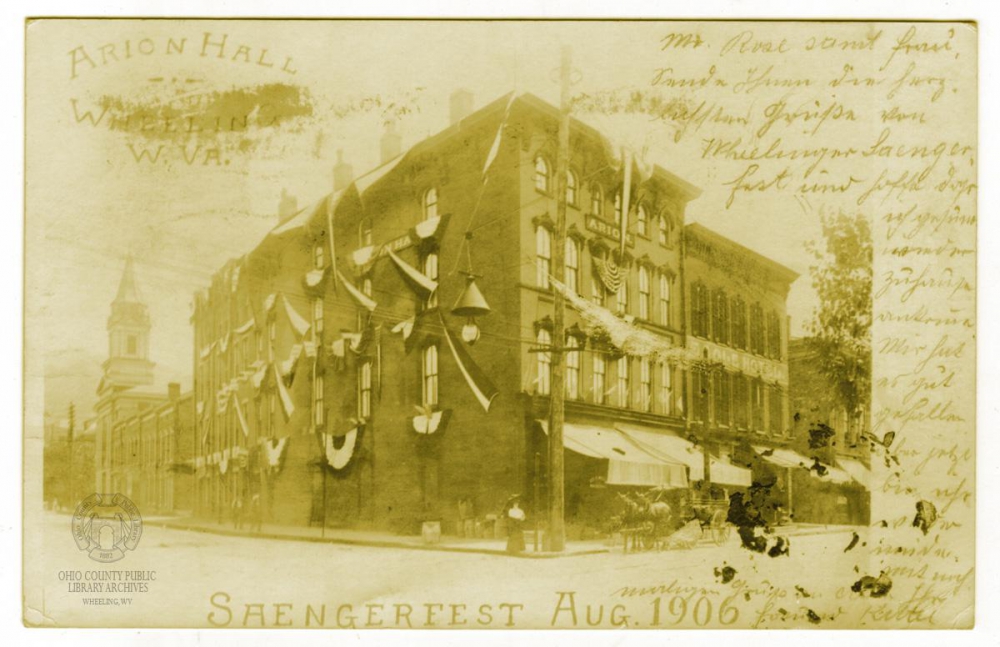

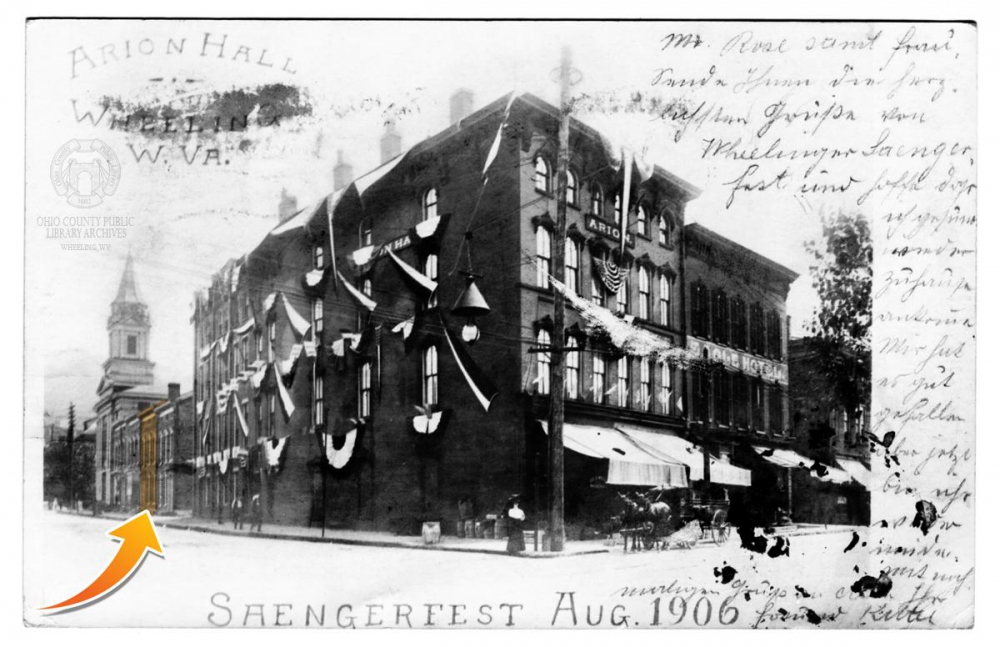

A History Mystery related to this Real Photo Postcard showing Arion Hall at 20th and Main during the 1906 Saengerfest was solved.

Arion Hall at 20th and Main Streets is decorated for the 1906 Saengerfest parade in this real photo postcard. Ohio County Public Library Archives.

Arion Hall at 20th and Main Streets is decorated for the 1906 Saengerfest parade in this real photo postcard. Ohio County Public Library Archives.When he saw the image, Jeremy Morris, Director of the Wheeling National Heritage Area Corporation (WNHAC), remembered that Dan Bonenberger, Associate Professor in the Historic Preservation Program at Eastern Michigan University was looking for such a rare period view of 20th Street (then known as Webster) looking east. Why? Because Professor Bonenberger and his class are doing research on noted Wheeling author Rebecca Harding Davis and her family, and the Harding Family once lived on 20th Street, between Arion Hall and Second Presbyterian Church. In fact, the Harding house, two up from Arion Hall, marked here with an arrow, is visible in the image.

Photographs of the Harding house are extremely difficult to find, and professor Bonenberger was very happy to see this RPPC.

In this instance, Archiving Wheeling worked just how we hoped it would when we wrote the mission statement: it helped an educator and a group of researchers to find material that will prove helpful to their research – material that they might otherwise have never seen.

In this instance, Archiving Wheeling worked just how we hoped it would when we wrote the mission statement: it helped an educator and a group of researchers to find material that will prove helpful to their research – material that they might otherwise have never seen.

We at Archiving Wheeling couldn’t be happier with the response to our German Days post. We look forward to continuing to solve history mysteries with all of your help and continuing to virtually connect Wheeling’s archival collections with researchers.