Bellaire-Wheeling Ferry Fights Bellaire-Benwood Bridge, Charon Sinks, June 1929

|

|||||

- From the Wheeling Intelligencer, Monday, June 24, 1929. © Ogden Newspapers; reproduced with permission.

Owner of Benwood Ferry Taking Last Stand Against New Bridge, Progress

J. H. ROBINSON DECLARES HE HASN'T BEEN ON THE RIVER FOR 50 YEARS FOR NOTHING

WILL CUT PRICES ON AUTOS AND PEDESTRIANS UNTIL "ONE OF US IS SUNK".

BELLAIRE, O., June 15 (NEA)—The oldest ferry of the Ohio river between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, which made its first trip when the Indians lurked among the vine-clad banks is fighting for existence. Its opponent is a $2,000,000 bridge corporation.

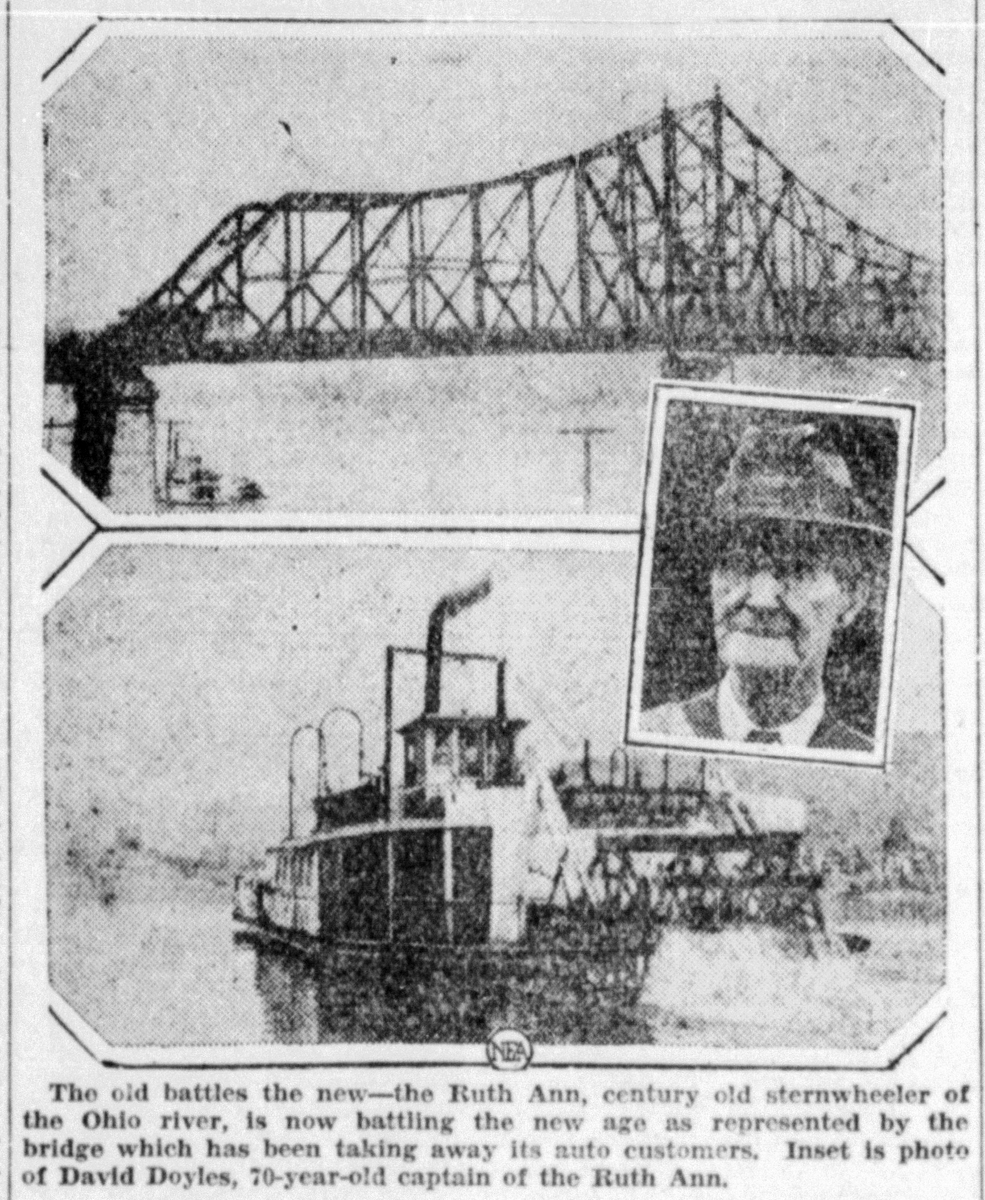

A 70-year old pilot, a 72-year-old engineer, and 50-year-old owner of the boat—an old sternwheeler, the Ruth Ann—are waging an up-hill fight to retain the prestige of the century-old ferry which has almost been forced into obscurity by the long steel girders and concrete pillars which represent progress in this motor age of ours.

In 1800, court records show, the Bellaire-Wheeling ferry was started. Three rowboats represented the sole possessions of the company. Time added other boats. Immediately preceding the Civil War, a wood-burning side-wheeler was purchased and the ferry was used as one of the links of the famous Underground Railroad for escaping slaves from Dixie.

Monopoly Is Shot

James H. Robinson, newspaper publisher, 10 years ago purchased the ferry, which was two boats, the Charon and the Ruth Ann, together with river rights on both sides of the Ohio. It did a flourishing business.

James H. Robinson, newspaper publisher, 10 years ago purchased the ferry, which was two boats, the Charon and the Ruth Ann, together with river rights on both sides of the Ohio. It did a flourishing business.

Last year the Bellaire-Benwood bridge was built, costing $2,000,000, Robinson has been seeing the handwriting on the wall, or in the river rather, dickered with officials of the bridge for the sale of the ferry.

Robinson contends bridge officials offered, in exchange for his river bank leases, to purchase the ferry when the bridge was completed. He agreed. Later the deal fell through and Robinson found himself still in possession of a sternwheelwheeler plying directly under the huge pillars of the new bride.

Robinson, after a conference with his pilot, Captain David Doyles, 70, and his engineer, Charles Lineger, 72, decided to "carry on."

The second day after the bridge-ferry battle started, the Charon sideswiped a pillar and sank in mid river. Then it was war. Rates for an auto over the bridge one way was 15 cents: Robinson made it 5 cents. Then the bridge—for all its $2,000,000 capital—cut rates to 25 cents round trip. The ferry still hauls autos for 10 cents round trip and passengers for 3 cents one way.

"We'll win yet," exclaims Captain Doyles defiantly. "They will either buy us out or we will sink 'em with cuts in rates. I ain't been on this river for 50 years for nothing. People ride where it costs less."

The whole Ruth Ann crew—three men—are loyal to Robinson. And Robinson says he will be on the river for another century or the ferry will. But at that, the traffic on the bridge is 10 times as heavy as on the ferry.

It's the old story of progress, and sooner or later the landmark of riverdom, around which so much of Ohio river history has been built, will be erased from the scene and carried down in the current through which its has been buffeted so long.

Tow Boat Charon | Riverboats | Transportation | Wheeling History Home | OCPL Home

Want to keep up with all the latest Library news and events?

Want to keep up with all the latest Library news and events?