by Dr. Christina Fisanick

As we collectively mourn the recent passing of Gordon Lightfoot, it calls to mind the connection between the singer-songwriter’s most famous ballad and Wheeling’s most celebrated park.

That song, of course, is “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” which commemorates one of the worst ship disasters in Great Lakes history. Lightfoot would later explain that his reason for writing the song was rooted in his belief that the tragedy hadn’t received enough attention. By the time the song was released in August 1976, less than a year after the SS Edmund Fitzgerald sank in Lake Superior, lawsuits against the ship’s owner, Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and its operator, Oglebay Norton Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio, had already been filed.

At some point following the disaster, Earl W. Oglebay’s grandson, Courtney Burton, Jr., who was then vice president and chairman of the board of Oglebay Norton, is said to have stormed into the Oglebay Mansion Museum and ripped an image of the doomed freighter off the wall and stormed back out without a word. Given that he spoke to no one that afternoon, the emotions guiding his actions are unclear. While the Wheeling Intelligencer paid no attention to the connection between Burton’s family company, Oglebay Norton Corporation, and one of the most infamous shipwrecks in recent history (featuring only AP articles about the incident itself), Burton himself certainly felt the sting as witnessed that day in the museum and surely as Oglebay Norton found itself at the center of multi-million dollar lawsuits filed by the families of the 29 men who drowned that fateful night.

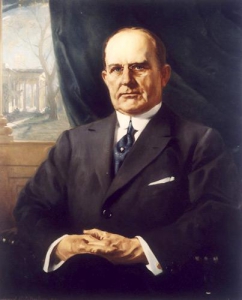

Earl W. Oglebay is known locally as the philanthropist who bequeathed his vast estate to the people of Wheeling following his death in 1926. Some students of local history might also know that he graduated from Bethany College and was at one point the youngest bank president in West Virginia history. But few people who have enjoyed the splendor of what is now Oglebay Park know that through his father’s investments in the Benwood Iron Works, Oglebay became one of Cleveland’s leading industrialists in the iron ore shipping industry.

Earl W. Oglebay is known locally as the philanthropist who bequeathed his vast estate to the people of Wheeling following his death in 1926. Some students of local history might also know that he graduated from Bethany College and was at one point the youngest bank president in West Virginia history. But few people who have enjoyed the splendor of what is now Oglebay Park know that through his father’s investments in the Benwood Iron Works, Oglebay became one of Cleveland’s leading industrialists in the iron ore shipping industry.

The origins of the Oglebay Norton Company stretch back to 1851 when two investors, Isaac Hewitt and Henry Tuttle, filled the need to ship iron ore from the recently discovered reserves in the Marquette Range of Michigan’s upper peninsula to industries in need. Doing so was quite a feat as water transportation was expensive, dangerous, and limited. Over the next three decades, use of steel steamships in favor of wooden vessels and improved waterways, including the opening of the Soo Locks, reduced the costs of shipping ore.

Unfortunately for Hewitt and Tuttle, the high demand for ore to make tubular pipes for the booming natural gas industry led to increased competition. In order to maintain their competitive edge and profit margin, they merged with a number of companies, including Oglebay-owned Benwood Iron Works just south of Wheeling, West Virginia. The new corporation, Tuttle, Oglebay and Company, established a vertically-integrated business model, which started with the extraction of iron ore from company-owned mines to processing it through several company-owned iron works where the finished company-forged pipes were then sold to the gas industry.

In 1889 Horace Tuttle died in a railroad accident and Oglebay bought out his heirs and dropped their name from the corporation. A year later Cleveland banker David Z. Norton partnered with Oglebay to form Oglebay, Norton, and Company. Among their many clients, the company brokered iron ore shipments for John D. Rockefeller, whose first job was as bookkeeper for Heweitt and Tuttle when he was still a teenager.

Following Earl Oglebay’s death, his nephew Crispin shared the helm with David Norton’s son Robert. Crispin Oglebay, whose name should be familiar to anyone who swims at Oglebay Park’s outdoor pool or enjoys events in the Pine Room, is credited by many for taking Oglebay, Norton, and Co. into a period of rapid expansion that lasted well into his presidency, which ended upon his death in 1949.

Immediately thereafter, Earl Oglebay’s grandson, Courtney Burton, Jr., was elected vice president of the company and from 1957 until shortly before his death in 1992, served as its Chairman of the Board. In the decades that followed, Oglebay Norton struggled to gain its footing under new officers in an industry being challenged by the influx of cheaply made foreign steel. Through the acquisition and creation of a number of new companies under its helm, though, Oglebay Norton survived this rough period by producing, shipping, and selling a diverse range of non-steel products.

Despite these achievements, however, the company would receive most of its attention during this era for its connection to what has become known as the the most famous shipwreck in Great Lakes history.

At the time of her launch on June 7, 1958, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest ship on North America’s Great Lakes. As part of its investment portfolio, Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, commissioned the Great Lakes Engineering Works to design and build the ship, which would haul taconite iron ore and other industrial minerals on the Great Lakes. The 728 feet long freighter was known by many nicknames that evinced her size and speed: Fitz, Mighty Fitz, Big Fitz, Pride of the American Side, Toledo Express, and Titanic of the Great Lakes. She rose 39 feet high and was 75 feet wide. Without cargo, the $7 million freighter weighed 13,632 tons.

Named after Northwestern Mutual’s president and chairman of the board, Edmund Fitzgerald, whose grandfather and uncles had been lake captains, the ship’s interior was luxurious, especially when compared to other lake freighters. With plush carpeting, air conditioning (even in the crew quarters), and two well-appointed dining rooms, the crew and its occasional passengers wanted little for dry-land creature comforts. Of course, the Fitzgerald’s nautical equipment and maps were state-of-the-art as well.

Soon after Northwestern Mutual leased the massive ship to Oglebay Norton on September 22, 1958 for a 25-year contract, the Edmund Fitzgerald became beloved by boat watchers, not just because of her size and record-breaking voyages, but because in part of Peter Pulcer, her so-called “DJ Captain,” who took her helm in 1966. Captain Pulcer entertained spectators day and night by piping music over the ship’s intercom and offering details about the ship to enthusiasts who lined the shores as the hulking freighter sailed by at top speeds of 16.3 miles per hour. Pulcer held that post until Captain Ernest McSorley took command of the vessel in 1972.

For 17 years the Fitzgerald worked the Great Lakes carrying freight from mines to factories in what would become 748 round trips, covering more than a million miles. Understandably, she was the flagship of the Oglebay Norton shipping fleet, and helped make the company a fortune during her time on the water. Tragically, her service and that of her crew was put to an abrupt end in early November 1975.

The Edmund Fitzgerald departed Superior, Wisconsin loaded with 26,116 tons of taconite iron pellets at 2:20 pm on November 9, 1975 bound for delivery to Zug Island on the Detroit River. The National Weather Service issued gale warnings for the area around 20 minutes after the ship set sail. Captain McSorley was no doubt concerned, but these kinds of warnings were not uncommon for the Great Lakes in November. In addition, McSorley was known as a “heavy weather captain,” who could manage his ships in rough waters. Not long after its departure, the Fitzgerald was joined in its voyage by another freighter, the Arthur M. Anderson, which was bound for Gary, Indiana. Until the Fitzgerald was lost, McSorley remained in radio contact with the Arthur M. Anderson’s captain, Jesse B. “Bernie” Cooper.

At 2:00 AM on November 10, the National Weather Service upgraded its warning from gale to storm, predicting winds of 45-50 knots (40-58 mph). Up until that time, the Fitzgerald had been following the Anderson. At around 3:00 AM, the Fitzgerald passed the Anderson, maintaining a distance of about 16 miles. Twelve hours later, at around 2:00 pm in the afternoon, wind speeds began to increase rapidly. According to the Anderson’s log, wind speeds reach 50 knots (58 mph) and at 2:45 PM, it started to snow. The Anderson lost sight of the Fitzgerald.

The Fitzgerald radioed the Anderson at 3:30 pm, reporting the loss of two vent coverings and a railing. The ship, McSorley added, was taking on water despite two of the six bilge pumps running full-time. Not long after McSorley’s dispatch, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) broadcast that the Soo Locks had been closed and that all ships should seek safe harbor. At 4:10 PM, the Fitzgerald radioed the Anderson for assistance–both of the Fitzgerald’s radar systems had failed. The Fitzgerald slowed its speed to allow the Anderson to get within 10-miles of the struggling ship so she could receive radar guidance.

The Anderson guided the Fitzgerald toward Whitefish Bay, but Captain Cedric Woodard of the nearby Avafors replied to McSorley’s request for information by noting that the radio beacon on Whitefish Bay was not working. Meanwhile, the Arthur M. Anderson logged sustained winds at 58 knots (67 mph). At some time after 5:30 PM, McSorley told Woodard, “I have a bad list, I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst seas I have ever been in.”

Not long after 6:00 PM, the Anderson was struck by winds as high as 75 knots (86 mph) and waves as high as 35 feet. Then, at around 7:10 pm on that ill-fated evening, the Anderson asked the Fitzgerald how she was doing, and McSorley replied, “We are holding our own, going along like an old shoe.” Cooper responded, “Okay, fine. I’ll be talking to you later.” Ten minutes later, the Anderson lost the ability to reach the Fitzgerald by radio or to detect her on radar. McSorley and his crew of 29 men were never heard from again.

Despite the incredibly dangerous weather conditions, the Arthur M. Anderson and her crew headed out in search of the Fitzgerald. Later they were joined by other ships, aircraft, and land rescue crews, but little more was found in the hours and days that followed than lifeboats and other debris. The families of the 29 crew members, most of whom were from Ohio and Wisconsin, waited in anxious limbo for days before getting official word from Northwestern Mutual that the Fitzgerald had sunk.

The wreck was found by U.S. Navy Lockheed P-3 Orion aircraft on November 14, 1975. The ship had split in two and lay 17 miles from the point of Whitefish Bay in Canadian waters. While many dives were made in the decades that followed, no bodies rose or were found. The bacteria normally used in the decaying process after death cannot survive the cold temperature of Lake Superior, so bodies do not naturally float to the surface. In essence, the Fitzgerald is an underwater tomb protected by laws regarding gravesite disturbances.

Biographies for most of the crew members, including photos and family remembrances can be found at the SS Edmund Fitzgerald Online.

In the days, weeks, months, and years that followed, the families and many others sought clues for why the Fitzgerald sank. While many theories have been put forth, even now, with more than 40 years of technological advances, a definitive answer to the question that has captivated so many for decades has yet to be found, which complicated the fight for insurance claims and survivor’s benefits.

When the Edmund Fitzgerald sank to her final resting place at 530 feet below the surface of Lake Superior, she was carrying a heavy load of ore. The value of the fully-loaded ship was estimated at $24 million, which would be about $130 million in 2023. Obviously, Northwestern Mutual and Oglebay Norton had suffered a major blow to their fortunes, but more losses to their companies’ coffers were just on the horizon.

Despite sailing in Canadian waters at the time of sinking, the Fitzgerald’s crewmembers were protected by the Jones Act, which ensured that because the ship was owned by an American company and flying the American flag at the time of sinking, then surviving family members were eligible to receive financial compensation for the loss of their loved ones. One week after the Edmund Fitzgerald sank, two widows of the deceased crew, Karen Pratt and Mary Poviah, filed a lawsuit against Northwestern Mutual and Oglebay Norton asking for $1.5 million. Not long after, a second suit was filed for an additional $2.1 million.

Fearing bankruptcy, Oglebay Norton filed a petition in the U.S. District court asking that their total liability be limited to $817,920 for any further suits filed by the families of crew members. The company’s lawyer, Thomas O. Murphy, arrived at that number based on the amount allowed by federal law: $60 per ton liability. The Fitzgerald displaced 13,632 tons.

The official U.S. Coast Guard report, released on April 15, 1977, noted that “the most probable cause of the sinking of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald was the loss of buoyancy and stability resulting from massive flooding of the cargo hold. The flooding of the cargo hold took place through ineffective hatch closures as boarding seas rolled along the spar deck.”

Although they are clear in stating that no definitive cause is found, this statement about probable cause pointed a finger directly at the crew for not closing the hatches properly. The Lake Carrier’s Association vehemently opposed their findings and issued a letter to the National Transportation Safety Board in September, 1977 arguing that the most likely cause was the Fitzgerald running aground in the Six Shoals Area, which was inaccurately marked on seafaring maps first created in 1919.

Numerous other theories abound to explain the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald, including weaknesses to the ship’s structure from previous incidents, lack of attention by freighter inspectors to ensure ship safety, and a massively oversized load, but one aspect of this complicated case remains clear: the weather played a tremendous role in the wreck. With winds and waves of near record-breaking dimensions, it is a wonder that the Fitzgerald is the only freighter that went down that fateful evening in November 1975.

Thankfully, the 29 crewmen did not die in vain. Following the USCG’s investigation into the sinking, many changes were made in ship safety, including load limits, weathertight compartments, crew training, onboard lifesaving equipment, search and rescue measures, and more. Perhaps most notably, the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald led to an increased likelihood of ships dropping their anchors in bad weather.

The staying power of the Great Lakes tragedy has been remarkable and is due largely to Gordon Lightfoot’s hit song, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” Lightfoot had heard about the ship’s sinking on CBC television in his home in Ontario, Canada, but it wasn’t until he read “The Cruelest Month,” an article detailing the sinking of the Fitzgerald that appeared in the November 24, 1975 issue of Newsweek that he felt moved to write about the incident. Following its release in August 1976, the unlikely pop song remained on the charts for 21 weeks, fully cementing the tragedy in the minds of anyone who listened to Top 40 radio.

It is hard to imagine today, but one of the reasons Lightfoot was so intent on writing the song was because, in his view, the wreck hadn’t been given the attention it deserved. To him, the tragedy deserved prominence because of the tremendous loss of life and the extent of the storm that ultimately took the freighter down. Lightfoot said he searched through newspaper reports of the wreck and created a timeline of the incident before overlaying the lyrics on an old Irish song, “Back Home in Derry,” he learned when he was around three years old.

Many of the families of the Fitzgerald crewmen expressed thanks to Lightfoot for commemorating their loss, but not everyone was pleased with the wreck being in the national spotlight. A source who was once close to Courtney Burton, Jr. recalls the Oglebay Norton executive banning the six minute and thirty-one second song from being played on Oglebay property and even attempting to get it banned from Ohio Valley radio stations.

Whether there’s truth to this recollection is a matter of speculation, but one thing is for certain, Lightfoot’s commitment to the memory of the Fitzgerald and her doomed crew remained throughout his career. After watching a 2010 Canadian documentary about the Fitzgerald’s sinking, he released a statement saying how grateful he was to the filmmakers for “putting together compelling evidence that the tragedy was not a result of crew error. This finally vindicates, and honors, not only all of the crew who lost their lives, but also the family members who survived them.”

While he did not re-record the song after viewing the 2010 documentary, he did change the lyrics during live performances to reflect that the sinking was not the result of crew error, a conclusion that had haunted him for years.

In the original song, Lightfoot sang:

When suppertime came, the old cook came on deck, sayin’,

“Fellas, it’s too rough to feed ya.”

At 7 p.m., a main hatchway caved in, he said,

“Fellas, it’s been good to know ya”

After March 2010, he sang:

When suppertime came, the old cook came on deck, sayin’,

“Fellas, it’s too rough to feed ya.”

At 7 p.m., it grew dark. It was then he said,

“Fellas, it’s been good to know ya.”

By all accounts Lightfoot stayed in close contact with the families and played at their reunions and memorial ceremonies. He insisted, however, that the focus remain on the crewmen and not on himself. On more than one occasion, he attended memorial services anonymously, sitting in the back of the venue so as to not draw attention to his famous face.

With support from the surviving family members, on July 4, 1995 the bell of the Fitzgerald was raised from the wreckage. While in rough condition from being submerged in Lake Superior for nearly two decades, it was cleaned and coated with the same kind of paint that was originally used on the bell. The original rope from the bell was used to fashion its clapper. The 200-pound, fully-restored brass bell is now on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at the Whitefish Point Light Station in Michigan, where it is rung 29 times every November 10 in memory of the men who died aboard the Fitzgerald.

But it was another bell, that of the Mariner’s Church in Detroit, that first started the tradition.

The day after the Edmund Fitzgerald sank, Rev. Richard Ingalls rang the bell 29 times, once for each life lost.

On Tuesday, May 2, 2023, the day after Lightfood died, the Mariner’s Church in Detroit rang their bell 30 times. Once for each of the crewmen who died aboard the Edmund Fitzgerald and one for Gordon Lightfoot, the balladeer who preserved their legacy for the world.

“Earl W. Oglebay.” (2023). Case Western Reserve University. https://case.edu/ech/articles/o/oglebay-earl-w.

“Oglebay Norton Company History.” (1997). International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 17. St. James Press. Reprinted: http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/oglebay-norton-company-history/

Fearing, Heidi. (2023). “John D. Rockefeller,” Cleveland Historical, https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/328.

Jonovic, Donald J. (1985). Iron, Industry, and Independence: A Biographical Portrait of Courtney Burton, Jr., American Industrialist and Patriot. Jamieson Press. Reprinted: https://case.edu/ech/articles/b/burton-courtney-jr

Quill, Greg. (2010). “Gordon Lightfoot Changes Edmund Fitzgerald Lyrics.” The Star,

https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/music/2010/03/25/gordon_lightfoot_changes_edmund_fitzgerald_lyrics.html

Thompson, Mark L. (1994). Queen of the Lakes. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Schumacher, Michael (2005). Mighty Fitz: The Sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald. New York and London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Cutler, Elizabeth Fitzgerald, and Walter Hirthe. (1983). Six Fitzgerald Brothers: Lake Captains All. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Marine Historical Society.

“Timeline of Events for the Edmund Fitzgerald.” (2022). SS Edmund Fitzgerald Online. https://ssedmundfitzgerald.org/fitz-timeline

Wolff, Julius F. & Holden, Thom (1990). Julius F. Wolff Jr.’s Lake Superior Shipwrecks. (2nd expanded ed.). Duluth, Minnesota: Lake Superior Port Cities. MacInnis, Joseph (1998).

MacInnis, Joseph. (1997). Fitzgerald’s Storm: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Charlotte, North Carolina: Baker and Taylor for Thunder Bay Press.

United States Coast Guard. (26 July 1977). “Marine Board Casualty Report: SS Edmund Fitzgerald; Sinking in Lake Superior on 10 November 1975 With Loss of Life (Report).” United States Coast Guard. hdl:2027/mdp.39015071191467. USCG 16732/64216.

National Transportation Safety Board. (4 May 1978). “Marine Accident Report: SS Edmund Fitzgerald Sinking in Lake Superior on November 10, 1975” (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

“Attorney Peter Riley to Speak Regarding his Work Investigating the Sinking of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald.” (2013). Schwebel, Goetz, and Sieben. https://www.schwebel.com/press/attorney-peter-riley-edmund-fitzgerald/

Mercante, James. (31 October 2006). “Lost Ship Resurfaces in New York Documents.” New York Law Journal. https://www.rubinfiorella.com/pdf/Edmund-Fitzgerald.pdf

Ley, Sean. (2023.) “The Fateful Journey.” The Great Lakes Ships Museum. https://shipwreckmuseum.com/the-fateful-journey/

“The Edmund Fitzgerald, 41 Years Later.” (7 December 2016). O’Bryan Law. https://www.obryanlaw.net/the-edmund-fitzgerald-41-years-later/

Brush, Mark. (10 November 2015). “Listen to Radio Transmission on the Night of the Edmund Fitzgerald’s Sinking.” Michigan Public Radio. https://www.michiganradio.org/arts-culture/2015-11-10/listen-to-radio-transmission-on-the-night-of-the-edmund-fitzgeralds-sinking

Schumacher, Michael, ed. (2019). The Trial of the Edmund Fitzgerald: Eyewitness Accounts from the U.S. Coast Guard Hearings. University of Minnesota Press.

“50 Years Of Music With Gordon Lightfoot.” (14 February 2015.) Weekend Edition,. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2015/02/14/386227473/50-years-of-music-with-gordon-lightfoot

Author bio: Christina Fisanick, Ph.D. is an associate professor of English at California University of Pennsylvania, where she teaches first-year writing, creative non-fiction, and digital storytelling. She is the author of more than 80 articles on local history and more than 30 books, including two memoirs, "Two-Week Wait: Motherhood Lost and Found" (2015) and "The Optimistic Food Addict: Recovering from Binge Eating Disorder." In addition, she is the co-author the forthcoming book, Digital Storytelling and Public History: A Guidebook for Educators. Fisanick lives in Wheeling with her son Tristan and two cats.

© Copyright 2025 Ohio County Public Library. All Rights Reserved. Website design by TSG. Powered by SmartSite.biz.