March 16, 1936. Wheeling, West Virginia.

The weather report in the upper left corner on the front page of the Wheeling News-Register was a little concerning, but certainly not dire. Not yet.

"HOURS OF RAIN This city has had a five hour rain starting at eleven o'clock last night with a pourdown [sic] for several hours. Streets were given a much needed washing."

Silver linings. But things would get worse -- hourly.

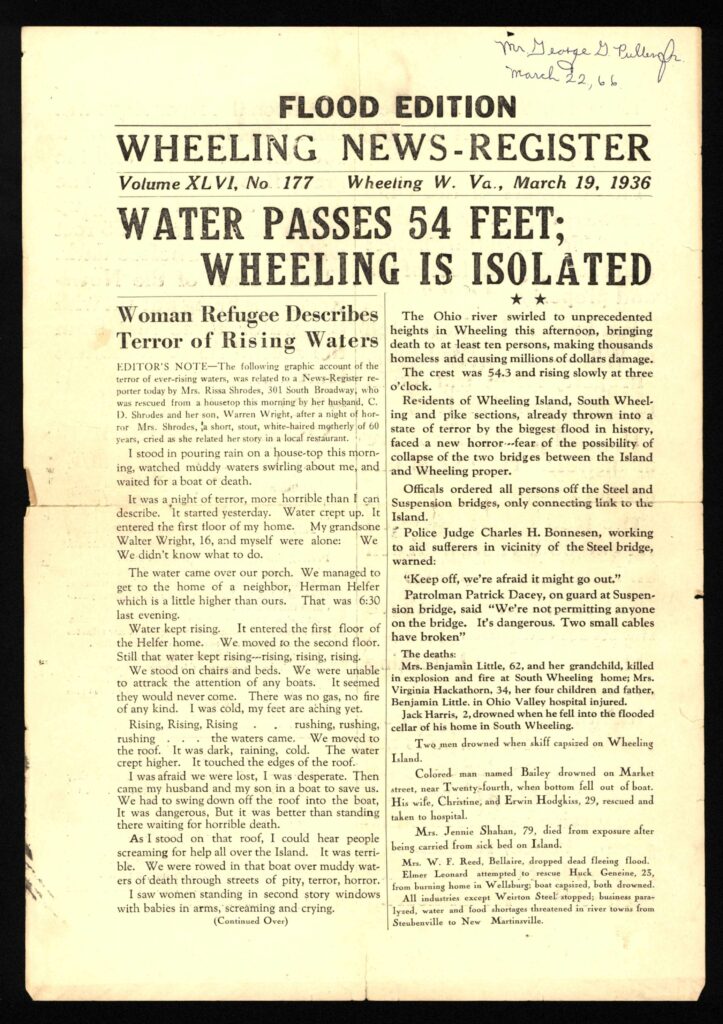

Their offices flooded, NR reporters used a small proof press to hand-set this crude but effective handbill for March 19.

Their offices flooded, NR reporters used a small proof press to hand-set this crude but effective handbill for March 19.

By St. Patrick's Day, the Wheeling Intelligencer noted that over an inch of rain had already fallen, and the temperature was dropping. By 9 AM that day, WWVA Radio had received its first high water warning from Pittsburgh with the prediction of water an alarming six feet above the 36 foot flood stage due to slam the town just two days later on Thursday, March 19. Moreover, it had been a severe winter along along the east coast. A combination of melting snow and ice combined with heavier than expected rain had bloated the Pittsburgh region's three rivers to unforeseen levels.

The radio station would later publish a "Flood Souvenir" that summed up the unprecedented result: "An avalanche of water poured into the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, which in turn emptied their swollen, raging torrents into the Ohio River." Wheeling, of course, was no stranger to massive Ohio River floods, its citizens having muddled through 52 feet in 1884, 51 in 1913, and 50 in 1907. But the 1936 flood was a behemoth from a different flood universe. The river would crest at 2 PM on March 19 at an astounding 19.5 feet above flood stage -- 55.5 feet at Wheeling -- inundating the entire city like never before, nor since, with floodwater covering more than 8 square miles: drowning the Island, much of South and Centre Wheeling, and downtown streets as far east as Chapline. Many houses and businesses were submerged up to their rooftops, trees were uprooted, joining menacing chunks of all manner of debris, propelled through the swift currents like juggernauts, roads and vehicles rendered unusable, with millions of dollars in damage done.

The Suspension Bridge and Steel Bridge were closed, and the Market Auditorium was converted to Red Cross headquarters, as well as a relief shelter and makeshift hospital. Utilities were shut down, supplies cut off, and diseases like typhoid threatened. Warwood and "Out the Pike" were cutoff from the business district. Hundreds of people were trapped in their homes, many without food or clean water or heat or electricity or phone service. More than 20,000 people were eventually driven from their homes, many rescued from rooftops by rowboats and other small watercraft able to negotiate the flooded streets. Seventeen people lost their lives. In fact, the flood pummeled the entire Upper Ohio Valley from Steubenville to New Martinsville and beyond. (See The Big One)  This photo used in the WWVA Flood book included this caption: "Rescue boat reaches safety after thrilling experience riding the raging currents. The rescued, a woman taken from a second story window of her home is being assisted to safety at the West end of the Steel Bridge."

This photo used in the WWVA Flood book included this caption: "Rescue boat reaches safety after thrilling experience riding the raging currents. The rescued, a woman taken from a second story window of her home is being assisted to safety at the West end of the Steel Bridge."

In Pittsburgh, where it is known as the "Great St. Patrick's Day Flood," 45 people were killed. And from New England to Washington, D.C. a great flood simultaneously hit the Potomac River, killing as many as 200.

The Ohio Valley was devastated. But heroes emerged. Many of them were facilitated by the teamwork of the Wheeling Chapter of the American Red Cross and WWVA Radio, whose 92.5 hours of continuous broadcasting during the darkest hours provided a beacon of hope and a touchstone for critical information no longer available from usually reliable sources like the newspapers. The News-Register's offices, for example, were flooded, forcing staff to abandon equipment for higher ground at their offices on 1500 Main Street. The intrepid reporters used a small proof press to hand-set a crude but effective "flood edition handbill" for March 19. But it was difficult to if not impossible to disseminate, and the paper would not return to regular production until Saturday, March 21.  Rev. Cropp of the Red Cross at the portable mic, connecting with and providing hope to flood-isolated listeners.

Rev. Cropp of the Red Cross at the portable mic, connecting with and providing hope to flood-isolated listeners.

Further complicating matters, in 1936, less than half of US homes had a working telephone, and the raging waters had downed most of the poles and overworked lines in any event. So radios became the most effective way to receive word about what was happening, to communicate messages to others, to try to locate or check on loved ones, and to organize donations and volunteers. And WWVA, the self-proclaimed "Friendly Voice Out of the Hills of West Virginia," was the station that stayed on the air through it all. As Rev. Frederick W. Cropp, Co-Chairman of the Disaster Committee, Wheeling Chapter of the American Red Cross wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Times newspaper dated March 28, 1936:

"The part played by the radio station WWVA in its ninety-two and one-half hours of continuous broadcasting is inestimable. With other forms of communication crippled by the rising demand or completely destroyed, the police, the Red Cross and other relief agencies sent out appeals for food, for volunteers and for other supplies of emergency nature. Over $50,000 was raised as a result of this Radio appeal. Food and the necessary supplies were rolling into Wheeling before the flood waters abated, wild rumors were crushed before they could spread their insidious work and the whole tri-state area was knit together in one common crisis."

Joining production manager Paul J. Miller, program director Walter Patterson, and announcers Carl W. Gustky, Paul Myers, Murrell Poor and Wayne A. Sanders, not to forget the numerous engineers who kept things running (including their own telephone lines along with portable transmitters), was Rev. Frederick W. Cropp himself. Amid periodic announcements and uplifting music by performers like Marybelle Dague, Capitol and Jamboree organist Vivian Miller, and Tex Harrison's Texas Buckaroos, Rev. Cropp would read on air, often from his remote microphone on the Steel Bridge, letters, notes, and telegrams from listeners searching for loved ones, people letting loved ones know they were OK, pleas for donations or help, and other vital information to help listeners get through the disaster. One on-air announcement, for example, warned "Don't Drive to Town just to see the flood. Don't come to the Hawley Bldg. Telephone Red Cross."

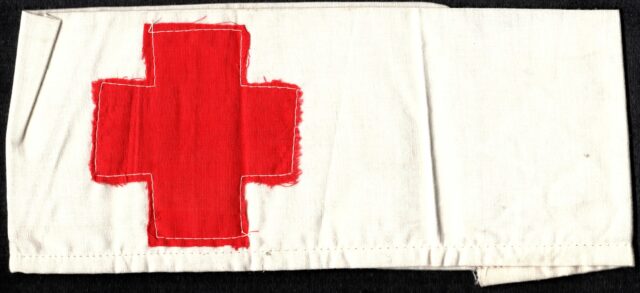

This Red Cross armband, possibly worn by Rev. Cropp, is part of the WWVA-Red Cross-1936 Flood Collection.

When WWVA later published its memoir of the event, 1936 WHEELING FLOOD SOUVENIR , the letters and notes were the missing component, the only one that could convincingly convey some measure of the fear and anxiety as well as the courage and self-sacrifice that characterized the 1936 flood in the Ohio Valley. Fortunately for us, and for posterity, more than 100 of the letters and notes (part 1, part 2, and part 3) read by Rev. Cropp during those fateful days in 1936 are now housed in the Ohio County Public Library's Archive as a part of the Capitol Theatre Collection of WWVA and Jamboree USA memorabilia. Many are now also part of an exhibit for a limited time in the main exhibit area of the Library, where you can view images, read the letters, and her them read by Library staff. Don't miss the "Lifeline" exhibit, part of the main Capitol Theatre and WWVA exhibit, now at the Ohio County Public Library. The letters and notes can also be viewed virtually in a slideshow below, or as a PDF, HERE.

New York, NY, September 12, 2002 -- Memorials are placed along the fence of St Paul's Church near Ground Zero from people all over the world. Photo by Lauren Hobart/FEMA News Photo

New York, NY, September 12, 2002 -- Memorials are placed along the fence of St Paul's Church near Ground Zero from people all over the world. Photo by Lauren Hobart/FEMA News Photo

Reading through the Red Cross and WWVA letters is an experience evocative of seeing the posters and flyers taped and stapled to walls and fences that showed up in the wake of the Sept. 11 tragedy and similar events, some typed, many handwritten and homemade, with photos and drawings of the missing and language such as “Please, have you seen. . ." In a manner foreshadowing these modern, spontaneous shrines of desperation and hope, Wheeling and the Ohio Valley used the only reliable communication method available to them under the circumstances -- the radio -- to reach out to the missing, the alone, and the terrified. One such letter came from Virginia Rowell of Cleveland, OH, who said she was "terrible worried" about her family members in Wheeling and Wellsburg, and that she would be "listening over the air for an answer." Meanwhile, a telegram from Pittsburgh asked for an update on Henry Lane, his wife and four children who were said to be "in critical condition on account of the flood." Another message marked "Urgent" described George Parks, "age 11. Curly reddish hair. Weighed 80 lbs. Missing since Wed night. Last see on 15th St." Another aspect of these messages is the hope and unity they convey. As with 9/11 and other national tragedies when scout groups were holding bake sales to benefit the victims' families, the Ohio Valley rallied to help its flood victims. A letter in shaky handwriting from a widow named Mrs. Adda Jones, for example, who said she had been an invalid for 2 years, nevertheless sent in a "small donation for the flood sufferers," while expressing her wish that it could have been more. In another touching letter, Earl Phillips, a self-described "poor farmer," unable to "give any help on account of sickness," sent two coats "to try to make somebody warm." He also asked to hear if his two daughters and their families were safe in Proctor, WV. A letter writer from New Philadelphia, OH offered to open her home to care for "two or three worthy children" if the police would bring them out. A woman from Short Creek sent clothes that once belonged to her "own dear little girl who slipped away 5 years ago." The United Mine Workers of the Wheeling district sent a large truckload of food and clothing while Dr. K.A. Rosenberg offered his services to the people of Wheeling Island: "Just get in touch with him and he will come to any flood sufferers." In Powhatan, a pumper fire truck was urgently called for to remove mud from the streets as "typhoid is menacing this town." Sometimes the news was good: "Mrs. Emolyn Fisher is safe at grandmas." But not all ended well. "Flash--the man at Alley 1-13," reads one typed note, "was dead when Dr. Gilmore arrived. His name was Jack O'Neill." In another note, Rev. Cropp or one of the other announcers struggled with the words to open the broadcast: "Red Cross flag flying over sleeping children and women. ..Angle 2-- City of Wheeling separated by water tonight. Fulton. South. Island. Warwood. Pike. NO OTHER DIVISION TONIGHT. United in community spirit. Wish you could see the groups working together." As previously mentioned, much as many of the haunting 9/11 posters are now housed at the 9/11 Memorial Museum in NYC, a large number of the letters and notes read by Rev. Cropp during those fateful days in 1936 are now housed in the Ohio County Public Library's Archive.

On March 21, as the waters began to recede, the true horror of the flood's violence slowly emerged. "Officials unable to estimate number of dead." The News-Register reported. "Devastating wreckage slows search for bodies. Wheeling dug into mud and wreckage today to remove the bodies of its flood dead." In its "Flood Supplement," dated March 29, 1936 under the headline "DAYS AND NIGHTS OF TERROR -- THE GREAT FLOOD OF '36.," the News-Register started the painful process of tallying the final casualties of the city's most devastating recorded flood. The first entry under "Flood Dead" told of the fate of two-year-old Jack Harris, who drowned after falling into the flooded basement of his family's home at Twenty-Fourth Street. A 48 year-old African American would-be rescuer named Ernest Bailey drowned on Twenty-fifth Street when the bottom of his boat collapsed. Two people were killed in an explosion. A few others died from "shock and exposure." The list went on. "Seventeen dead in the Wheeling district," the News-Register reported, "$5,000,000 damage in Wheeling alone; hundreds of casualties; half a dozen houses washed away and hundreds of others damaged..." By March 22, the city was under martial law.  For Wheeling, the known death toll was 17. The physical/structural recovery would take months, even years. The psychological recovery was incomplete. The Great Flood of 1936 was a traumatic event and would haunt those who survived it to their own graves. The wounds would never fully heal, even with the passage of time. Even those, like the author, born many years after the flood waters receded, grew up hearing enough about the flood from our elders that even we have felt its enduring trauma. Like it or not, the "Big One" is more or less a permanent part of Wheeling's DNA.

For Wheeling, the known death toll was 17. The physical/structural recovery would take months, even years. The psychological recovery was incomplete. The Great Flood of 1936 was a traumatic event and would haunt those who survived it to their own graves. The wounds would never fully heal, even with the passage of time. Even those, like the author, born many years after the flood waters receded, grew up hearing enough about the flood from our elders that even we have felt its enduring trauma. Like it or not, the "Big One" is more or less a permanent part of Wheeling's DNA.

Capitol Theatre Collection of WWVA and Jamboree USA memorabilia of the Ohio County Public Library Archives.

Radio Station WWVA Wheeling Flood Souvenir, 1936.

Wheeling Intelligencer editions, March 16, 1936 to March 23, 1936.

Wheeling News-Register editions, March 16, 1936 to March 23, 1936.

Wheeling News-Register,1936 Flood Edition Handbill, Vol. XLVI, No. 177, March 19, 1936. See also.

Wheeling News-Register, "Flood Supplement," Vol. XLVI No. 189, March 29, 1936.

© Copyright 2025 Ohio County Public Library. All Rights Reserved. Website design by TSG. Powered by SmartSite.biz.