By Sean Duffy

Born Drusilla Petticord on March 4, 1865 on a West Liberty farm, she grew up to become Mrs. Drusilla “Drucie” Petticord Bauer-Turner, a respected baseball “authority” and Wheeling’s most formidable and perhaps West Virginia’s only female baseball “magnate.”

When a reporter asked her in 1917 why she took such an interest in the sport, Drucie retorted: “My boy that is a foolish question. Why do young children like to play with toys? Why do girls like to dress dolls? I used to watch the boys play in the back yards in all sorts of uniforms and – well, I always liked to see everything natty and nice, so I took the boys under my care…” (1)

In a 1925 interview, she addressed her own passion for the sport: “I used to play on a girls’ team when I was younger. We lived in the country and had nothing else to do. I used to pitch and catch. Later I thought a team would do well in Wheeling so I organized one, and managed it myself.” (2)

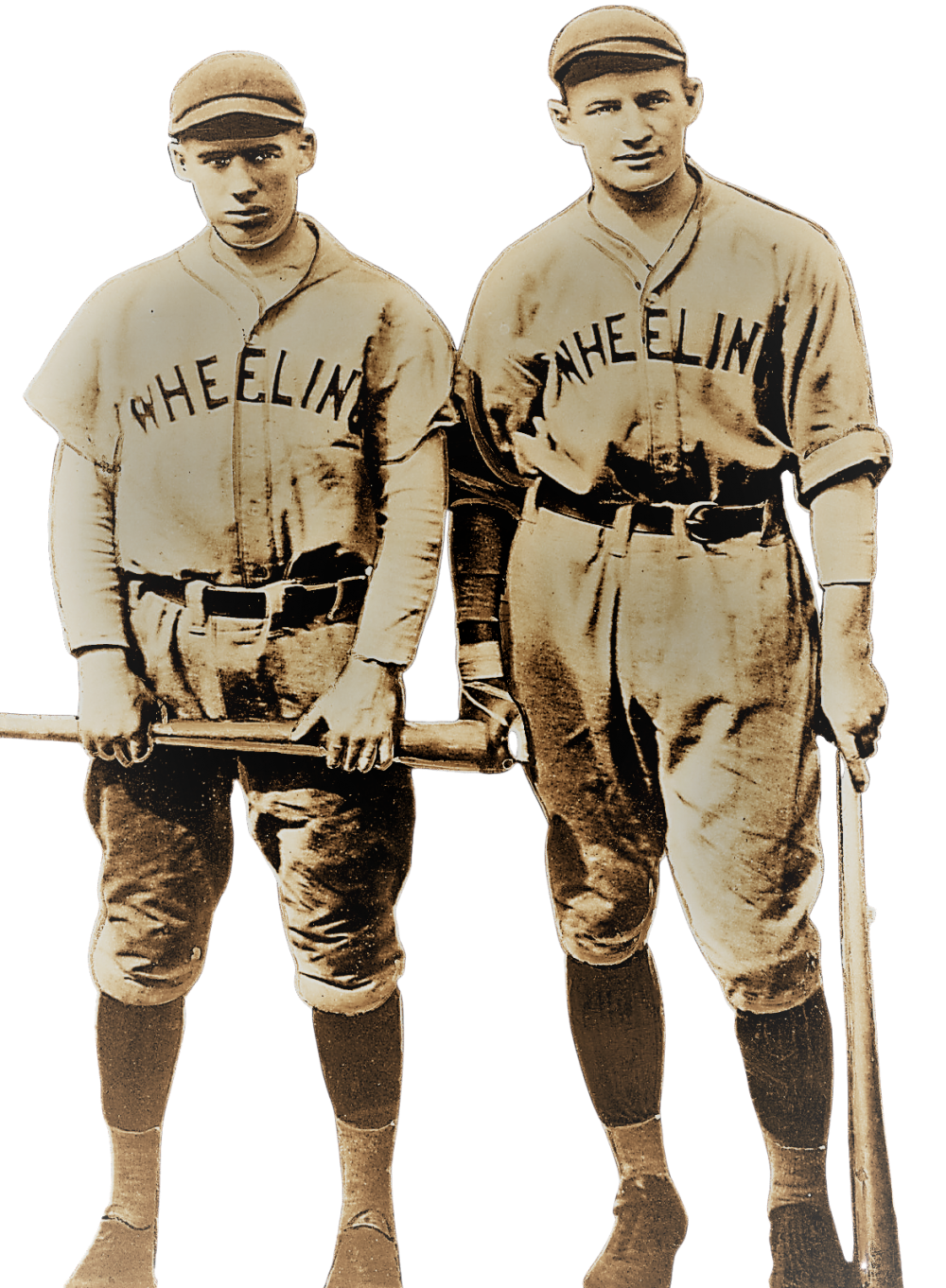

Indeed, Drucie managed three teams named “Bauer”: a junior, an intermediate, and a semi-pro team in the Inter-City League, playing against the McConkeys (Macks), Stroehmann, Carroll, Home, Follansbee, Fulton, Shadyside, Steubenville, and Virginia clubs on fields from Forty-Seventh Street in South Wheeling (Pulaski), north to League Park in Martins Ferry, Steubenville, and at Fulton and Tunnel Green in between.

Drucie was certainly tough to have earned such success in the male-dominated world of sandlot baseball, but, as yet another male reporter stressed, she was not at all a “hard-boiled masculine sort” as one might expect, instead she was “very womanly” with an “attractive feminine voice.” (3)

She ran her baseball empire from her home and business at 876 McColloch Street (located in an area later claimed by Wheeling Tunnel and I-70). Alternately described as a grocery store, restaurant, and boarding house, the “Foundry” was the teams’ meeting place for all of the Bauer home games, usually played a few blocks away at Tunnel Green or around the creek at Fulton Field, later to be christened ”Bauer Park.”

Drucie Petticord married Charles Bauer in 1887. The earliest mention of any Bauer baseball squad appears in the May 26, 1906 Wheeling Intelligencer when the Charles Bauer club played the Jim Woods on the Mt de Chantal grounds. The same report also included a challenge from the Bauers to “any team between fourteen and sixteen years for a game on Decoration Day for $25 a side.” Thus did the Bauers first engage in the standard early twentieth century method for scheduling local sandlot baseball games: by throwing down the gauntlet in print in the newspaper. (4)

The spring and summer editions of the Intelligencer and Register were peppered with such challenges under the header, “Amateur Baseball.” In the May 17, 1910 Intell. For example, the LaBelles challenged “any 17-year-old team, the Benwood juniors preferred, for a game Sunday.” Answers were also to be made through the newspaper, or sometimes by telephone. Meanwhile the “Boys of Goosetown” accepted the challenge of the R.A. Steins on the Fulton grounds and the Bauers, after defeating the Edgwood Cat Fish 10-9, challenged “any 15-year-old amateur teams in the city.” (5)

Even as “trash talking” recently dominated sports headlines in 2023 courtesy the women’s NCAA basketball tournament, these early baseball newspaper ads prove the phenomenon is not new. In 1913, for example, the Bauers Juniors asked why the “W.H. Paulls did not show up Sunday at Fulton. They must be afraid of losing their reputation.” Ouch. (6)

In 1911, the Glenlawn Juniors challenged the H. Noltes, proclaiming: “If you fellows are afraid to play us shut up. You have only defeated us once, but you can’t do it again.” (7)

A survey of amateur baseball challenges and game reports reveals fascinating array of team names, some with more mysterious origins than others, such as the Stone Town Sluggers, Busy Bees, Bellaire Shamrocks, East Wheeling Knockers, Loveland Stars, Wellsburg Giants, Go Easy Juniors, Mules, Walkovers, Brooksides, and the Cat Fish.

After winning another Central League championship in 1909, the Wheeling Stogies, the town’s semi-pro ball club collapsed, both in terms of wins and finances. By 1913, the Smokes were out of the Central and by 1914, Wheeling could no longer boast of a professional baseball team. So, high performing amateur clubs, like the Bauers and the McConkeys, stepped up to the plate fill the void for baseball-hungry fans. (8)

As a woman in a man’s sport, the press immediately took an interest in Drucie. In April 1918, her Bauers senior club merged with the Stroehmanns (“two of the fastest teams in this locality”) to create “one of the best ever gathered together in this city.” During this era, “fast” became a synonym for good. The Stroehmanns were the reigning Inter-City League champions, but the consolidated team would play under the name Bauers. Drusilla Bauer, “the well-known East End grocer” and “perhaps the greatest woman fan in the state” was to finance the team at a cost of about $1000 (about $20,000 in 2023 dollars), with John “Yocke” Jacobucci as manager. Drucie had hesitated to field a team so soon after the United States had declared its intention to join the European war, but decided that “Uncle Sam wanted the boys to get as much training as possible at home.” (9)

As a woman in a man’s sport, the press immediately took an interest in Drucie. In April 1918, her Bauers senior club merged with the Stroehmanns (“two of the fastest teams in this locality”) to create “one of the best ever gathered together in this city.” During this era, “fast” became a synonym for good. The Stroehmanns were the reigning Inter-City League champions, but the consolidated team would play under the name Bauers. Drusilla Bauer, “the well-known East End grocer” and “perhaps the greatest woman fan in the state” was to finance the team at a cost of about $1000 (about $20,000 in 2023 dollars), with John “Yocke” Jacobucci as manager. Drucie had hesitated to field a team so soon after the United States had declared its intention to join the European war, but decided that “Uncle Sam wanted the boys to get as much training as possible at home.” (9)

Also in 1918, Drusilla married Francis Turner, so in 1919, the team name changed to Bauers-Turner. At the end of that season, a controversy arose over competing claims of the Bauers-Turner and McConkey (or Macks) nines for the Valley championship. Each claimed they beat the team that beat the team. “If both records were published,” Bauers Manager John “Yocke” Jacobucci wrote in a letter to the editor, “and the list of teams met compared, the McConkeys would appear as a first class amateur club, and the Bauers a leader in semi-pro ranks.” He then wagered $500 for a three game contest with the Macks. (10) The Dillonvale Indians then jumped into the fray, claiming the title for themselves, dismissing the Macks, whom they had defeated two out three games, and challenging the Bauers to a game. (11) The Bauers and Indians met at League Park in Ferry to settle the issue, but the game was rained out with the score 0-0. The Indians had apparently “imported” a group of minor league ringers, paying the mercenaries $200. The Bauers called for a rematch, but Dillonvale refused unless the game was at Dillonvale where it was said the Wheeling team would have needed “a large company of guards” because the Indian fans were “hard-boiled.” (12) Another challenge was issued for an October matchup. But when the chaotic dust and bravado cleared, the Bauers-Turner nine, winners of their last 13 games (final record: 17-7-2), were crowned champs and declared “the greatest aggregation seen upon a local lot since the Central league left Wheeling.” (13) A trophy was made by jeweler O.C. Genther and put on display in his shop. (14)

The rivalry was intensified for 1920 when the Bauers and Macks played for the championship in a best of five series. The Bauers won game one 4-3 in 10 innings (15) and game two 8-1 at League Park (16). The Macks took game three, 4-3 on August 2 at Tunnel Green and the Bauers made it three out of four, defeating the Macks in come from behind fashion, 7-4 at League Park on August 22. (17) An 11 inning, 4-1 win over the Martins Ferry Eagles on Sept. 12 earned the Bauers their second consecutive city championship. (18)

The rivalry was intensified for 1920 when the Bauers and Macks played for the championship in a best of five series. The Bauers won game one 4-3 in 10 innings (15) and game two 8-1 at League Park (16). The Macks took game three, 4-3 on August 2 at Tunnel Green and the Bauers made it three out of four, defeating the Macks in come from behind fashion, 7-4 at League Park on August 22. (17) An 11 inning, 4-1 win over the Martins Ferry Eagles on Sept. 12 earned the Bauers their second consecutive city championship. (18)

The Bauers were favored again in 1921. When Drusilla was asked during a preseason interview why she continued to finance baseball teams, she replied: “I have always loved baseball and think it the cleanest sport in the world. Years ago when I saw boys playing in the streets, I thought it was a shame they did not have a place to play where they would not be likely to get run over by the street cars and other vehicles. I started out about ten years ago by having a junior team composed mostly of boys whose parents were customers of my store. The boys soon became proficient and in a few years I made them my intermediate team and took on a new junior aggregation.” (19) She went on to credit the hiring of “Yocke” for making the Bauers the great success they were and the reason Drucie decided to lease Martins Ferry’s League Park for her teams for the 1921 season, which turned out to be their best to date, with three out of four wins over the Macks and another city championship. (20)

Also in 1921, the Bauers began a rivalry with the Homestead Grays, the popular barnstorming Negro League team from Pittsburgh, winning one of the three games the teams played that season. (21) This success prompted Drucie to field a football team, which opened against Martins Ferry Post 35 American Legion squad at League Park. The Bauers staged a come from behind victory 13-10, with two second half TD passes by Duffy. (22)

The Bauers and Grays played six more times in 1922, splitting the series three games apiece. The Bauers closed with an impressive doubleheader double-victory over the storied Grays franchise before a record crowd at Fulton Park, winning 6-0 and 7-5. (23) For a look at the rivalry between the Macks and the Homestead Grays, see Donna Halper’s recent article. (24)

The Bauers closed the 1922 season at 14-5, losing to the National league Boston Braves by only one run, but with no games played against the Macks. (25)

That raised the issue of playing for another city championship, and Drucie balked. Her explanation speaks volumes about her character and motivations. In an article titled, “Woman Owner Declines Any City Series,” the Wheeling Register quoted her: “I only conduct a baseball club to provide week-end amusement for those people who like the game and because I, myself, am fond of the sport. I had one experience with post-season games two years ago when the Bauers and McConkeys played a series. It created so much bad feeling and stirred up so many personalities I said then and there so long as I had anything to do with the club, I would never consent to a series of this kind. It injured the game and actually hurt my business. So far as I can see, the only purpose for arranging the series is to make money. I am quite satisfied with our patronage this season. The fans have been very liberal at Fulton Park and most of all they have maintained the best order and conduct there. That is what I desire above all else, that is why my club has always booked games with outside teams. I have nothing more to say in the matter and hope this statement will terminate any further discussion of a series so far as the Bauers are concerned.” (26)

That raised the issue of playing for another city championship, and Drucie balked. Her explanation speaks volumes about her character and motivations. In an article titled, “Woman Owner Declines Any City Series,” the Wheeling Register quoted her: “I only conduct a baseball club to provide week-end amusement for those people who like the game and because I, myself, am fond of the sport. I had one experience with post-season games two years ago when the Bauers and McConkeys played a series. It created so much bad feeling and stirred up so many personalities I said then and there so long as I had anything to do with the club, I would never consent to a series of this kind. It injured the game and actually hurt my business. So far as I can see, the only purpose for arranging the series is to make money. I am quite satisfied with our patronage this season. The fans have been very liberal at Fulton Park and most of all they have maintained the best order and conduct there. That is what I desire above all else, that is why my club has always booked games with outside teams. I have nothing more to say in the matter and hope this statement will terminate any further discussion of a series so far as the Bauers are concerned.” (26)

In April 1923, Drucie obtained a permit to enlarge the grandstand at the Fulton Park for $2500.00 (about $44,000 in 2023). (27) Her team donned nifty new top of the line grey and black uniforms made by Spalding as they posted an early victory against a team managed by Pirates legend Honus Wagner, the Bauers winning impressively 9-0 at Fulton before a crowd of 4,000.(28) The Bauers lost a few weeks later in “Hair-Raising” fashion to the Homestead Grays, 4 to 3, (29) then came from behind to beat the Turners of Pittsburgh 6 to 5. (30) In June, they opened a three games series with the highly touted “world semi-pro champion” Beaver Falls Elks, winning 9-7 as Joe Swetonic “pickled the sphere with the cushions cluttered” for a grand slam. (31) The Bauers were trounced in game 2 with the Grays, 17-7, then lost 5-1 to the North Side Board of Trade team from Pittsburgh with a centerfielder named Art Rooney, who finished with three hits. (32) Just two years later, Rooney would play with his brother Dan for the revived Wheeling Stogies team, partly owned by Mrs. Bauer (see below).

Despite starting a former Pirates pitcher named Myrl Brown, the Bauers were again drubbed by the Grays on July 22, 15-2. (33) An 8 to 1 loss to the Ward Independents of Charleston in front of 1000 Valley Camp Coal employees had them on a rare 4 game skid. (34) After several rain outs, the Bauers dropped another to the Grays, 9 to 4. The team finally recovered their stride, beating the semi-pro world champ Beaver Fall squad 10-3 to claim that series 2 games to 1. And on September 23 before a crowd of 4500 at Fulton Park, the Bauers again defeated the Homestead Grays in a doubleheader, 1-0 in 16 innings, and 1-0 again in game two with a walk-off home run by right fielder Hughes. (35)

Despite starting a former Pirates pitcher named Myrl Brown, the Bauers were again drubbed by the Grays on July 22, 15-2. (33) An 8 to 1 loss to the Ward Independents of Charleston in front of 1000 Valley Camp Coal employees had them on a rare 4 game skid. (34) After several rain outs, the Bauers dropped another to the Grays, 9 to 4. The team finally recovered their stride, beating the semi-pro world champ Beaver Fall squad 10-3 to claim that series 2 games to 1. And on September 23 before a crowd of 4500 at Fulton Park, the Bauers again defeated the Homestead Grays in a doubleheader, 1-0 in 16 innings, and 1-0 again in game two with a walk-off home run by right fielder Hughes. (35)

Drucie upped her promotional game in 1924, scheduling exciting exhibition games against the Boston Braves,

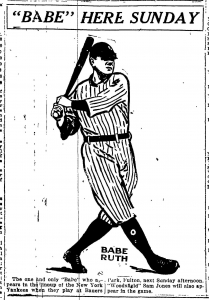

Drucie upped her promotional game in 1924, scheduling exciting exhibition games against the Boston Braves,  Yankees, and Pirates. (36) The team opened the season by once again facing off against Honus Wagner’s Carnegie Elks at the newly expanded Fulton Park, winning 9 – 8 on the strength of Jack Snyder’s triple. Unfortunately, the Boston game was a rain-out, as was the highly anticipated matchup with Babe Ruth’s Yankees scheduled for June 1. The Babe was coming to town with his “Black War Club” and the game was to start sharply at 2:30 “if Babe has fully digested the luncheon menu Col. George Phillips will serve him prior to leaving for the par.” But alas, the “big sporting feature of the year” was not to be. “N.Y. Yankees Vote Mrs. Bauer Local Club Owner Gamest Sport in the Country,” the Register headline trumpeted, “Wanted to Go Through With Exhibition Game And Toss Away a Couple of Thousand Dollars…” Indeed, Drucie was ready to play ball for the fans who showed up, another testament to her character. “Mrs. Bauer-Turner, who sponsors the Bauer baseball club of this city can rightfully be classified as a ‘dead game sport’ even though she is a woman.” Yankee manager Huggins refused, fearing injuries to his star players. The Yankees were impressed by her grit, and promised to come back to Wheeling. (37)

Yankees, and Pirates. (36) The team opened the season by once again facing off against Honus Wagner’s Carnegie Elks at the newly expanded Fulton Park, winning 9 – 8 on the strength of Jack Snyder’s triple. Unfortunately, the Boston game was a rain-out, as was the highly anticipated matchup with Babe Ruth’s Yankees scheduled for June 1. The Babe was coming to town with his “Black War Club” and the game was to start sharply at 2:30 “if Babe has fully digested the luncheon menu Col. George Phillips will serve him prior to leaving for the par.” But alas, the “big sporting feature of the year” was not to be. “N.Y. Yankees Vote Mrs. Bauer Local Club Owner Gamest Sport in the Country,” the Register headline trumpeted, “Wanted to Go Through With Exhibition Game And Toss Away a Couple of Thousand Dollars…” Indeed, Drucie was ready to play ball for the fans who showed up, another testament to her character. “Mrs. Bauer-Turner, who sponsors the Bauer baseball club of this city can rightfully be classified as a ‘dead game sport’ even though she is a woman.” Yankee manager Huggins refused, fearing injuries to his star players. The Yankees were impressed by her grit, and promised to come back to Wheeling. (37)

Meanwhile, in between, the Bauers lost 8-2 to their old nemesis, the Homestead Grays. They evened the score with the Grays on June 22, winning 13-2 with Frank Noel on the mound. The Bauers lost a surprise exhibition to Philadelphia’s major league team, 5 to 3 on July 13, then defeated the Grays 15-6 a week later, with Noel once again the starting pitcher. Instead of playing the Pirates on August 24 as announced, the Bauers were trounced by the Uniontown Elks as ace pitcher Frank Noel was badly shelled, final score 10 -1. Noel lost again on Labor Day to the Grays, 8-3. Both the team and their ace got off the schneid a week later, beating National Tube of McKeesport 3-2. Overall a success with 11 wins and 4 losses, even though a financial failure due largely to rain-outs, the 1924 season would prove to be the team’s and Drucie’s last, at least as sole proprietor. But the Woman Baseball Magnate wasn’t quite finished. (38)

The Intelligencer reported on Oct. 14 that the Homestead Grays won 106 of 148 games in the 1924 season, a record for a sandlot team. According to the newspaper records we have, the Bauers played the Grays (a major league quality Negro League team) 17 times in four years, winning 7 and losing 10. Not bad.

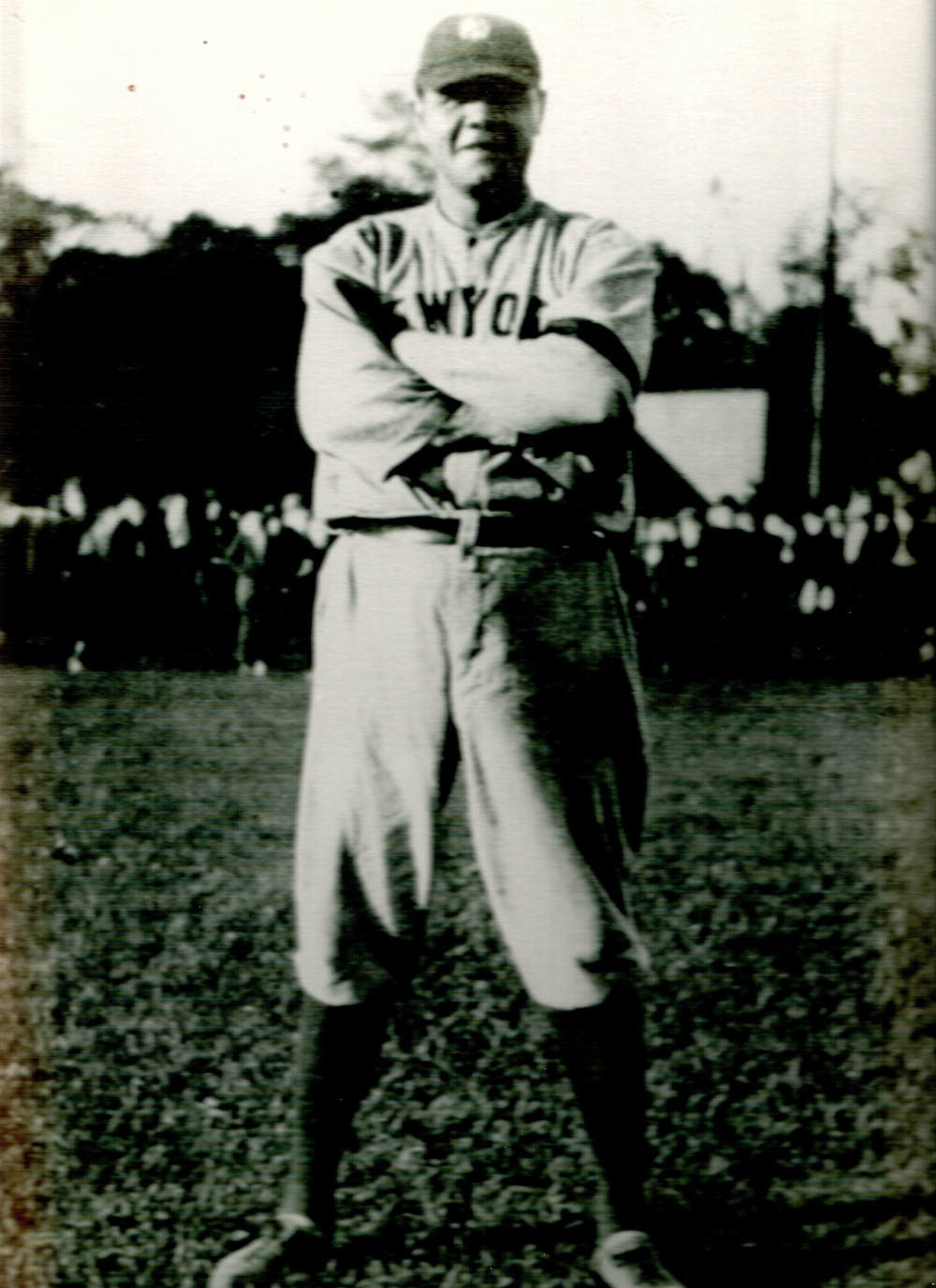

In February of 1925, enticed by the prospect of a return of the “Central League” to Wheeling, Drucie waited to schedule games and commit her money, eager to invest in a new Wheeling semi-pro club. (39) Enter Pittsburgh sportswriter Richard “Dick” Guy, who created the new Mid-Atlantic League and revived the Stogie franchise for Wheeling, bringing in gritty players like the scrappy 24 year-old centerfielder (and team captain) Art Rooney of Pittsburgh and his athletic brother Dan. “Mrs. D. Bauer Turner,” the Intell. Reported, “former owner of the Bauer club, is half-owner of the Wheeling Mid-Atlantic outfit.” (40) The resurrected Stogies would play home games at Bauer Park in Fulton. Other Mid-Atlantic franchises included Fairmont and Clarksburg, WV; Johnstown, Pittsburgh, Charleroi, Uniontown, Altoona, and Scottsdale, PA; and Cumberland, MD.

In February of 1925, enticed by the prospect of a return of the “Central League” to Wheeling, Drucie waited to schedule games and commit her money, eager to invest in a new Wheeling semi-pro club. (39) Enter Pittsburgh sportswriter Richard “Dick” Guy, who created the new Mid-Atlantic League and revived the Stogie franchise for Wheeling, bringing in gritty players like the scrappy 24 year-old centerfielder (and team captain) Art Rooney of Pittsburgh and his athletic brother Dan. “Mrs. D. Bauer Turner,” the Intell. Reported, “former owner of the Bauer club, is half-owner of the Wheeling Mid-Atlantic outfit.” (40) The resurrected Stogies would play home games at Bauer Park in Fulton. Other Mid-Atlantic franchises included Fairmont and Clarksburg, WV; Johnstown, Pittsburgh, Charleroi, Uniontown, Altoona, and Scottsdale, PA; and Cumberland, MD.

The Stogies opened on the road in Fairmont in 1925, with Mrs. Bauer scheduled to “curve the first ball across the plate” after a celebratory “auto parade.” (41) The Stogies won the game 6-2, while “Manager Art Rooney set his players a good example,” by doing “everything but eat the horsehide.” (42) The home opener at Bauer Park against Cumberland was rained out, so the team actually opened at home on May 28 against Clarksburg, winning that game 10-4 in “the first twilight game ever staged by a league” in Wheeling. (43) The new era Stogies were off to a torrid start, leading the league in wins. Unfortunately, it was downhill from that point. By season’s end, the Stogies were 39-62 — good for second to last place. On the positive side, the Rooney brothers played well. Art led the Mid-Atlantic in games played at 106, runs at 109, and stolen bases with 58. He finished a close second in batting average at .369. Brother Dan, who played catcher, batted .359 with 35 doubles and 18 home runs. (44)

Dan left baseball for the priesthood, becoming Franciscan Father Silas Rooney at St. Bonaventure. Art, who apparently lacked only the arm strength to play in the majors, continued to play semi-pro base ball in Pittsburgh (both he and Dan played as late as 1927 for the Twin Cities team coached by Honus Wagner); (45) managed boxers like Tom Murphy of Canonsburg, then shifted to football with the Steubenville Hope Harveys team (Art played HB and Dan QB). (46) Known as “The Chief,” Art later bought a football team called the Pittsburgh Pirates that eventually changed its name to the Pittsburgh Steelers. The rest, of course, is history. Homestead Grays manager Cumberland Posey was a mentor of Art Rooney, who served as a pallbearer at Posey’s funeral.

As for Drucie, in October 1925, she was dubbed a “Wheeling Baseball Authority” by the Intelligencer, which interviewed her about expectations that season for the Pittsburgh Pirates. “I still expect Pittsburgh to win the pennant,” she predicted. “This is the first year since 1913 that Mrs. Turner has not managed a baseball team,” the writer explained. (47) For the record, Drucie proved prescient. The Pirates did run away with the pennant, then defeated the Washington Senators to win the World Series 4 games to 3.

By 1927, the Stogies had purchased Bauer Park from Drucie for $7000, or about $121,000 in 2023 dollars. (48)

Nine years after the big rain ran them off, Ruth and the Yanks really did play in Fulton.

Drusilla “Drucie” Petticord Bauer-Turner, Wheeling’s Woman Baseball Magnate, died October 7, 1933 in Wheeling Hospital at the age of 68 after a long illness. She was survived by a sister and four brothers.

A member of the Church of God, Drucie was buried at Stone Church Cemetery. (49)

In May of that year, the Yankees finally kept their promise, returning to Wheeling nine years after their rainout against the Bauers, with stars like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig to play the Stogies (by then a Yankee farm club) in an exhibition game at what was then known as Stogie Park in Fulton. The park that Drucie built, teemed with estimated crowd of 10,000, including people jamming the rooftops of surrounding houses, and kids who climbed atop the park fences. This raucous throng was thirsty for a home run by Ruth or Gehrig, but the only homer in the game was hit by Wheeling catcher George Dickey, whose brother Bill played for the Yanks. The Stogies also managed a triple play involving Gehrig. The game finished with a downpour, a section of the bleachers gave way, mildly injuring a few men, and Babe Ruth (who did rap two doubles) entertained the crowd by doing a summersault in the mud to stop a hit. When the rainfall cleared, the world champion Yankees had prevailed, 6-2 . (50)

In May of that year, the Yankees finally kept their promise, returning to Wheeling nine years after their rainout against the Bauers, with stars like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig to play the Stogies (by then a Yankee farm club) in an exhibition game at what was then known as Stogie Park in Fulton. The park that Drucie built, teemed with estimated crowd of 10,000, including people jamming the rooftops of surrounding houses, and kids who climbed atop the park fences. This raucous throng was thirsty for a home run by Ruth or Gehrig, but the only homer in the game was hit by Wheeling catcher George Dickey, whose brother Bill played for the Yanks. The Stogies also managed a triple play involving Gehrig. The game finished with a downpour, a section of the bleachers gave way, mildly injuring a few men, and Babe Ruth (who did rap two doubles) entertained the crowd by doing a summersault in the mud to stop a hit. When the rainfall cleared, the world champion Yankees had prevailed, 6-2 . (50)

Presumably, Drucie would have been too ill to attend. But was she honored or recognized in any way at her park? The record, so far, does not speak.

Twenty-two years later in August 1955, two former Bauers players, including the great pitcher Frank Noel (a one-time NY Giants prospect) and infielder Jimmy Ford were inducted into the “Ohio Valley Old Timers [Baseball] Club.” Mrs. Bauer was recognized as the person who built Fulton Field. (51)

Had I alone been conducting the research inspired by a real photo postcard of an older woman standing with a baseball team, labeled “Lucilla Bauers…Sponsored Team…McColloch Street,” I might have stopped there — with the above — thinking I’d found the whole story.

But this is a learning opportunity for anyone using digital newspaper databases like the one on the Ohio County Public Library’s website to keep looking. One never knows what wrinkles a more thorough search might reveal.

In this instance, for example, my colleague Erin Rothenbuehler did the initial research, and in her signature manner, found far more than she was expecting about the life of Drusilla Bauer—evidence of a quirky life beyond baseball.

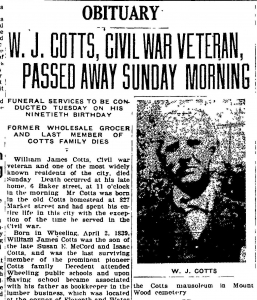

It all seems to have started in 1912 when a feisty 75-year-old Civil War veteran, retired wholesale grocer, pool room proprietor, and landlord named W.J. Cotts filed a complaint with the Police Court claiming Drucie’s first husband, Charles Bauer, had deliberately placed an obstruction in the street to block his team of horses from hauling dirt. The matter was thrown out. (52)

Cotts then petitioned Wheeling City Council, accusing Charles Bauer, of “running a speakeasy and gambling joint…without paying a state or city license” at his house on Baker Street, which obstructed access to Cotts’s house on Carroll Street. Cotts asked that Bauer’s house be removed. It seems various courts had ruled in Bauer’s favor, but Cotts refused to let the matter rest. (53) In 1913, a report claimed Bauer was indicted for running a speakeasy on evidence furnished by Cotts.

In March 1913, the Intelligencer reported that Cotts had been taken into custody by the sheriff on the complaint of Mrs. Charles Bauer, “and thus the old Cotts-Bauer feud which has enlivened East Wheeling life for some time, was renewed.” Drucie accused Cotts of striking her with a rake and threatening her with bodily harm. Cotts was fined $20 and costs and a one year peace bond was issued. Cotts “who has been in court more times than most people would care to appear” appealed. (54)

In August of the same year, Charles Bauer was fined $20 and costs for allowing men to gamble in his boarding house. A sheriff, who had received a tip (one can make an educated guess here), saw men fleeing a chip-covered poker table in the house. Bauer and the other men claimed they were playing “seven-up” for beers, using the chips as markers. (55)

In April 1914, Drucie faced an indictment by a Wheeling grand jury for selling cigarettes to minors, presumably from her store the Foundry on 876 McColloch Street. (56) In May of the same year, Cotts was back, accusing Mrs. Bauer of stealing furniture from him. The court found for the Drucie. (57)

In February 1920, Cotts struck again when he accused the Turners of violating a city ordinance by throwing trash in the alley behind their home. The case was dismissed for lack of evidence. (58)

Perhaps still reeling from the speakeasy affair, in June, 1933, (just a few months before her death) Mrs. Bauer’s store at 876 McColloch Street was listed in the newspaper as one of the polling places for the special election for voting on the repeal of prohibition. (59)

As for Cotts, his named continued to appear in the newspapers year after year as he filed lawsuits against the city; wrote letters to the governor complaining about the state of gambling laws; petitioning city council to build a retaining wall to protect his property saying, “act or resign”; and accusing a man of assaulting him and biting him in his pool room. In 1924, at age 87, the feisty Cotts made page 11 with his complaints, claiming he had “several crows to pick with the city,” most of which had to do with damage he claimed the Wheeling and Elm Grove Railway company had done to his property. (60)

As for Cotts, his named continued to appear in the newspapers year after year as he filed lawsuits against the city; wrote letters to the governor complaining about the state of gambling laws; petitioning city council to build a retaining wall to protect his property saying, “act or resign”; and accusing a man of assaulting him and biting him in his pool room. In 1924, at age 87, the feisty Cotts made page 11 with his complaints, claiming he had “several crows to pick with the city,” most of which had to do with damage he claimed the Wheeling and Elm Grove Railway company had done to his property. (60)

In 1928 at age 89, Cotts was arrested for allegedly beating his daughter as he tried to leave her home where she was apparently caring for him. (61) Cotts died in March 1929 in his Baker Street home at age 90. (62) Ornery even in death, he had requested in his will that he be buried in his parents’ Mt Wood vault in a sheet with no casket. (63)

So, with further investigation we learn that Mrs. Drusilla Bauer, while staking her claim as Wheeling and West Virginia’s only woman baseball magnate, was also dealing with a full blown East Wheeling feud with a locally infamous and persistently accusatory neighbor named W.J. Cotts.

None of that insanity detracted from Drucie’s amazing accomplishments in a male-dominated sport during a patriarchal era.

Generally: Wheeling Intelligencer and Wheeling Daily Register, 1906 through 1933. Thanks to Erin Rothenbuehler for initial research.

1 Wheeling Intelligencer, March 8, 1917, pg 7.

² Ibid. Oct. 12, 1925, pg. 9.

³ Ibid.

4 Ibid. May 26, 1906, pg. 7.

5 Ibid. May 17, 1910, pg. 7.

6 Wheeling Daily Register. July 30, 1913, pg. 9.

7 Ibid. Aug. 8, 1911, Pg. 9.

8 Akin, W. West Virginia Baseball: A History, 1865-2000. McFarland. 2006.

9 Intell., April 8, 1918, pg. 7.

10 Ibid. Sept. 10, 1919, pg. 7.

11 Ibid. Sept. 29, pg. 7.

12 Ibid. Sept. 22, pg. 7.

13 Register, Jan. 12, 1920, pg. 4.

14 Ibid. Sept. 23, pg. 8.

15 Intell. July 24, 1920, pg. 7.

16 Ibid. July 26, 1920, pg. 7.

17 Register, Aug. 23, pg. 6.

18 Intell. Sept. 13, pg. 7.

19 Jan. 24, 1921, pg. 4.

20 Ibid. and Register, Sept. 26, 1921, pg. 6

21 Intell., April 22, 1921, pg. 9.

22 Ibid. Oct. 8, 2021, pg. 6.

23 Register, Sept. 16 and 18, 1922, pg. 8.

24 Halper, D. “April 12, 1925: Homestead Grays open season by defeating McConkey Macks” accessed online at https://bit.ly/43C9MgS

25 Register, Sept. 22, 1922, pg. 11.

26 Ibid, Aug. 19, 1922, pg. 9.

27 Intell. April 5, 1923, pg 15.

28 Register, April 23, 1923, pg. 8.

29 Ibid, May 28, 1923, Pg. 8.

30 Intell, June 4, 1923, Pg. 7.

31 Register, June 18, 1923, pg. 9.

32 Register, July 16, 1923, pg. 8

33 Intell., July 23, 1923, Pg. 6.

34 Register, July 30, pg. 8

35 Register, Sept. 24, pg. 8.

36 Ibid. May 11, 1924, pg. 15.

37 Ibid. June 3, 1924, pg. 8.

38 Ibid. Sept. 23, 1924, pg. 9.

39 Ibid. Feb. 12, 1925, pg. 9.

40 Intell. May 5, 1925, pg. 10.

41 Register. May 5, 1925, pg. 9.

42 Ibid. May 21, 1925, pg. 11.

43 Intell. May 29, pg 10.

44 Ibid. Oct 21, 1925, pg. 13.

45 Ibid. May 27, 1927, pg. 16.

46 Register, Oct. 11, 1926, pg. 7.

47 Intell. Oct. 12, 1925, pg. 9.

48 Register, May 8, 1927, pg. 25.

49 Intell. Oct. 9, 1933, pg. 5.

50 Register and Intell. May 15 and May 16, 1933, various.

51 Register, Aug. 24, 1955, pg. 20.

52 Ibid. Dec. 28, 1912, pg. 2.

53 Ibid.

54 Intell. March 14, 1913, pg. 10.

55 Ibid. Aug. 5, 1913, pg. 14.

56 Register, May 10, 1914, pg. 13.

57 Ibid. May 16, 1914, pg. 3

58 Intell. Feb. 7, 1920, pg. 14.

59 Register, June 26, 1933, pg. 13.

60 Intell. July 14, 1924, pg. 11.

61 Register. Oct. 19, 1928, pg. 15.

62 Intell. April 1, 1929, pg. 5.

63 Ibid. Aug. 6, 1929, pg. 20.

© Copyright 2025 Ohio County Public Library. All Rights Reserved. Website design by TSG. Powered by SmartSite.biz.