Like most kids who grew up in Warwood, I walked, biked, or drove by a place called Centre Foundry & Machine Company thousands of times without really knowing what went on behind its nearly transparent, sun-bleached, hospital blue-green, corrugated metal and cinder block walls. Passing the building at any hour of the night, a kid like me might hear the bone-shivering shriek of metal on metal as an orange-red glow irradiated the thin walls, piercing through the rivets and rips and broken window panes like a laser show, adding to the mystery.

What the hell were they doing in there?

The answers to that question turned out to be far more amazing than I could have imagined. This remarkable little plant had been doing business in Wheeling for a century and a half by the time I was a curious kid and for nearly two centuries by 2023, when that business was unceremoniously ended. The foundry was born in 1840 when Martin Van Buren was President and Abraham Lincoln was a 31-year-old lawyer and leader in the Whig Party. The American Civil War was still two decades away. Rebecca Harding, who would later expose the harshness of life for workers in the iron mills as a groundbreaking writer, was a nine-year-old child living in Centre Wheeling, quite near the location of the foundry. Were some of the men she later wrote about who would “skulk along like beaten hounds” actually inspired by those she saw headed to work at the foundry? Likely. There was as yet no wire bridge suspended over the Ohio River, the more famous LaBelle Iron Works would not exist for a dozen more years, the B. & O. Railroad was 13 years from coming to town, Wheeling would remain a city in Virginia for another quarter century, and Wheeling Steel would not exist for nearly a full century.

Over time, even as its men forged monstrously heavy iron castings and ingots, Centre Foundry crafted, for example, cannon balls for Union troops (1), nail machine parts for La Belle (2), castings for the Suspension Bridge (3), decorative iron trim for shutters and doors during the restoration of West Virginia Independence Hall, aka, the Custom House (4), and a life-sized steelworker who now stands in Steubenville (5). When you ask old-timers (like me) what Wheeling used to be like, they might sigh and say, “We used to make things.” Indeed Wheeling, once the keystone of a region known as “The Workshop of the World,”(6) made quite an array of “things,” such as glass, tile, steamboats, stogies, and beer. But what those old-timers might list first is what Centre Foundry, in all of its incarnations, did best—they made iron. Those laborers were, with all due respect to the beloved semi-professional football club, Wheeling’s REAL Ironmen.

Sadly, in 2023, operations at this time-tested and until recently thriving original Wheeling manufacturing center came to a screeching halt. And in May, 2024, the Ohio County Public Library’s Archives team and the video team from Wheeling Heritage had the privilege of being invited to take a guided tour of what was left of Centre Foundry with veteran guide Frank VanSyckle.

See video of our tour by Johnathon Porter and Dillon Richardson of Wheeling Heritage. See photographs of the tour by Heritage and OCPL staff.

Centre Foundry’s last owners then donated numerous old patterns as well as a rich collection of archival photographs, ephemera, and ledgers that are now part of the Library’s archival collections. View the Centre Foundry Collection on the Library's Flickr page. Many of these artifacts have been installed in our new exhibit, “Molding America: Wheeling’s Real Ironmen” alongside artifacts from OVGH and OVMC under the banner: “A Fond Farwell to Two Wheeling Stalwarts.”

Stalwarts indeed. But why did Centre Foundry -- one of our city’s most durable and ancient industrial businesses -- close? To try to answer that question, we must begin at the beginning.

An ad for Centre Foundry from the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer of Aug. 8, 1853, focusing on iron stoves, sinks, and grates.

An ad for Centre Foundry from the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer of Aug. 8, 1853, focusing on iron stoves, sinks, and grates.

It all started two decades and one year before the American Civil War when, in 1840, brothers James and H. Andrew Baggs erected a foundry on the corner of John and Fourth Streets (now 16th and Chapline), coincidentally near the current location of the Ohio County Public Library. Baggs Foundry and its 10 employees produced small iron castings, using sand molds (more on the process below) to make things like iron stoves and boiler grates. (7) It was at this point through the next move that young Rebecca Harding may have seen the workers skulking from her bedroom window. The name "Centre Foundry" was in use by Baggs as early as August 1853. (8)

In 1855, the company was purchased by brothers Alexander and Charles Cecil, who moved it to what is now 2011 Main Street (near Main Street Bank) in Centre Wheeling, officially adopting the name “Centre Foundry” in 1860, after operating as Cecil Bros. After the Civil War, with J.R. McCourtney and Edwin Hobbs running things, cast iron and heavy machinery was manufactured for rolling and cut nail mills, as well as parts and engines for steamboats. The foundry was incorporated in 1881. (9)

To make “gray iron castings,” (10) Centre Foundry used patterns, typically made of wood, packed into an iron box known as a “drag” and filled with special hardening silica “green sand” and clay. When the pattern was removed, a void remained that was then fired and hardened using a “blackening agent.” A cupola furnace was used to melt iron – 9 tons in one day. Master moulder William McElroy led the effort to make large castings for Crescent Iron Works as well as cast iron house fronts and gates. (11) By 1881, an English immigrant pattern-maker named John Young had acquired a controlling interest in the company. Though John Young died in 1892, the Young family would own the company until 1979, when Dyson-Kissner-Moran Corporation took over. (12)  British pattern-maker John Young bought Centre Foundry in 1881. His family would operate the plant for decades.

British pattern-maker John Young bought Centre Foundry in 1881. His family would operate the plant for decades.

During the latter 19th-century, Centre Foundry continued making nail machines, castings, rolls, and nail plate shear, shifting to molds and castings of 500 pounds and heavier after the turn of the century. The name was changed to Centre Foundry & Machine Company, incorporated around 1902.(13) Advertisements of the period boasted “cast-iron house fronts,” “ornamental fencing,” “window lintels and sills,” “ore pulverizers,” “muckbar and nail plate sheers,” “gearing, pulleys, and all kinds of machinery castings.”(14) In 1923, the foundry moved from Main Street to its 11-acre site in South Warwood, nevertheless retaining the name “Centre.” By 1927, the company employed 85 men and made 20 tons of castings per year. During this time, they made repair parts to the specifications of purchasers all over the United States (15). By 1928, employment had increased to 100 and by 1938, the company employed 150 people making 800 train car loads of cast iron pots, stamping and drawing dies, and machinery castings per year. (16)

Significantly, in 1952, Katherine T. Young became the first and only female president of Centre Foundry.

The CWW logo was stamped on castings made at the time.

The CWW logo was stamped on castings made at the time.

In 1964, Centre Foundry acquired Washington Mould, Machine, and Foundry of Washington, Pennsylvania (founded 1917) and in 1967 Wadsworth Foundry of Wadsworth, Ohio (also founded in 1917). This expansion to the “CWW” group significantly increased and diversified the product portfolio for Centre Foundry to include ingot molds, massive grey iron castings of up to 70 tons, slag pots, and blast furnace runners. A newsletter titled “CWW Casting Around” began publication. Yet by 1979, both subsidiaries were closed, largely because they could not competitively meet new environmental standards. “That closed a lot of companies,” Frank stated. “But it needed to be done. No doubt. I can remember the cupolas when they ran back in the 60s, how the soot would come out, and if the wind was blowing right, it would come north onto the lower part of Warwood. And my mother used to be so upset. She’d be hanging clothes out there, and little black spots would be on some of them.” (17) According to Frank, caustic pots like this one were used by the steel companies to "dump their steel in there, and the impurities would come to the top and flow into another pot. I made one that was 13 by 13.”

According to Frank, caustic pots like this one were used by the steel companies to "dump their steel in there, and the impurities would come to the top and flow into another pot. I made one that was 13 by 13.”

At the Warwood location, Centre Foundry long produced ingot molds (16 to 20 a day) and castings, primarily for the steel industry. “That’s what my father did when he first started there,” explained Frank VanSyckle. “He was a rammer. Ingot molds were used by the steel companies. They could pour their alloys into it, uh, their steel into it…and what was good about that was, once it cooled, it would shrink. The iron molds that we sent to them, they would dissipate the heat of the steel, and also could be re-used over and over. And what was nice, at that time, our product that we sold to them could be re-used multiple times and that was the reason why we were so good at what we did.”(18) Frank VanSyckle Sr.

Frank VanSyckle Sr.

Frank’s father worked at Centre Foundry for roughly 46 years, from 1950 through 1995. Frank himself worked there from 1977 through 2023, when the foundry closed--nearly a century between them. “Centre Foundry made the cast iron molds of all different shapes and sizes. The Specialty Steel companies would pour their specialty alloy products into our ingot molds. The steel company then would take their product out of the ingot once cooled. [They] could take their product and roll it into different sizes to make railcar wheels, or depending on the alloys in these rolls, they might be making surgical instruments, or space shuttle parts, airplane parts, appliances, etc.” (19) Even through the 1960s, the melting facilities consisted of old-style cupolas. During the nineteenth century through mid to late twentieth centuries, cast iron was produced the old way, using coke and limestone to melt pig iron at 2,300 degrees in preparation for casting. This was not a clean process, producing prodigious amounts of air pollution. But a cleaner method existed. (20)

On our tour, we saw a large amount of coke still near the cupolas, where it had sat unused for decades. That was because, in 1973-74, two modern, clean-burning, electric Ajax Channel Induction furnaces with a total capacity of 55 tons, were installed on more than 2 million pounds of concrete. They were supplied with electricity from power stations located both north and south of the plant. This eliminated cupola use (for the most part, as we'll soon see) and helped the foundry to meet federal air quality standards under the Clean Air Act. (21) [gallery columns="2" size="shareaholic-thumbnail" ids="12693,12873"] The original transformer is still there today. “69,000 volts come down off the hill from AEP,” Frank recalled. “I wouldn’t want to pay that bill every month…You could hear the humming of it, it was so strong.” (22)

The cupolas as they look now.

The cupolas as they look now.

But even modern electric furnaces were not 100% reliable. “It was unbelievable, that I actually got to work on one of those cupolas when we lost a furnace," Frank explained. "There was no iron to prime a new furnace [when one went down after a fire], so the way you did that was we used the cupola, with the old-style air induction and coke, limestone, and pig iron.* And you would melt all that. And we made enough to pour into the ladle plus another half ladle to pour into the new furnace to prime it. But the smoke it made! Oh. We got fined—I think it was $10,000 a day. We took the hit. We had to...If you don’t have molten metal, you don’t work.”(23) The company eventually removed the air induction system, eliminating any possible use of the two cupolas to avoid additional fines. *Why pig iron? Pig iron gets its name because when it was poured the runner was called a “sow” and the ingots on each side resembled suckling piglets. The arrangement of the molds resembled a litter of nursing piglets. (24)  Pig iron stacked in the Warwood yard, circa 1948.

Pig iron stacked in the Warwood yard, circa 1948.

The cupolas continue to sit unused in the old foundry as of this writing. Tom Hoffman, a former Center Foundry employee, approached me about a year ago after the plant closed. Tom wanted to talk to me about an idea he had that he wanted me to pass along to the right people--people who appreciate our heritage and are in a position to make a difference in terms of preserving it. I promised him I would do so, and sent an email to the people I thought might be able to take action.

The Clinton Blast furnace at Station Square speaks powerfully to Pittsburgh's industrial heritage. Surely Wheeling deserves something similar.

The Clinton Blast furnace at Station Square speaks powerfully to Pittsburgh's industrial heritage. Surely Wheeling deserves something similar.

Tom mentioned the Clinton blast furnace, on display for many years now near Pittsburgh's Station Square. If you've seen it up close, you know what an impressive exhibit of Pittsburgh's former industrial prowess it makes. It is a fitting tribute to the Steel City’s proud history, making a powerful statement that is not to be ignored. Other examples from Pittsburgh include the the blast furnace lungs, also at Station Square, and the incredible Carrie Blast Furnaces National Historic Landmark — Rivers of Steel at Homestead. Tom believes that the cupola furnaces in Centre Foundry could make a similar statement for Warwood. The ones in Centre Foundry must date at least to the late 19th century, and they are quite impressive. Tom envisions salvaging one cupola and placing it at Heritage Port -- or alternatively, I would suggest, near the new visitor center, or near the Centre Foundry site, or somewhere.

Workers load up the giant "O" from the OVGH sign for storage. Courtesy WTOV.

Workers load up the giant "O" from the OVGH sign for storage. Courtesy WTOV.

The furnaces are quite massive and would require a crane and semi-truck to move. We understand it will be expensive and unlikely, but we wanted to plant the seed of an idea. I agreed with him then, and I still think the idea has merit, assuming the possiblity still exists. Much like the tower of letters at OVGH [a successful effort has been made to save those as well], such a thing would be an amazing piece of public art that would dazzle and draw visitors. It would be challenging, but worth it, we believe. We currently have little in terms of public art to memorialize Wheeling's own industrial past. This would be an epic answer to that omission. But time is of the essence. It is not known how long before everything is dismantled and sold for scrap. That would be unfortunate. We’ve lost countless treasures like this before, and we are running out of opportunities. In fact, I can't think of another quite like this. Consider this the seed of an idea. Perhaps some readers will be willing to help this idea grow. Feel free to drop us a line.

This sample of the iron trim made for the restoration of the Hall is now part of the archive and exhibit at OCPL.

This sample of the iron trim made for the restoration of the Hall is now part of the archive and exhibit at OCPL.

The finished iron trim can be seen here, over the shoulder of Gov. Pierpont (Travis Henline).

Maria Shriver visited the foundry in 1972 when her father, Sargent, was campaigning as George McGovern’s running mate for vice president of the United States. (25) And here one cannot help but conjure images of Shriver's future (and now ex) husband lowering himself into molten iron in Terminator 2, thus committing robot suicide in an effort to save the future for humanity. Ok, fine, it might have been steel.

That was fun, but 1973 was even better.

1973 was a banner year for Centre Foundry. Workers had spent two years experimenting and working with the original plans of architect Ammi B. Young to reproduce cast iron trim on exterior steel doors for the rebirth of Wheeling's Custom House as West Virginia Independence Hall. Although the trim could not be reproduced in the same way it was originally created in Italy, with skilled craftsmen creating patterns in wood (the modern version used plastic), the end result was remarkably accurate. The process required a much smaller scale, more intricate type of casting than Centre Foundry workers were accustomed to, but these adaptations offered learning opportunities. After the iron trim was installed on the steel, the entire door was painted to resemble wood grain, as was done with the original doors. (26)

That same year, Centre Foundry donated some of its property at North 24th Street in Warwood for the city to build a playground, where I would spend a huge number of my summer and not-so-summer days as a kid. (27) Behind the playground, over a small embankment of sand there was a huge sand pit where Centre foundry dumped sand and blocks of petrified sand from their molds. It was full of long strips of rusty metal, and huge lumps of what looked like black glass [according to Frank, these were “slag caps” or “taps”—basically hardened slag material that had been skimmed off the iron - yummy]. Frank had something to do with that mess. “My dad was a truck driver for a long time before he became ‘company.’" he said, "And I went with him as a little kid…He’d back that truck up and he’d have these slag caps—we call them taps—They would take the iron and skim it off, all the slag, and you’d get iron in it too. And they were so heavy. And he’d put that on his truck with some sand, and he would travel up to 24th Street and dump those up here. He backed up to the edge and scared me to death. I thought he was gonna go over the edge…When it would slide out, it would bounce on the back end and I’m thinking, ‘Oh my goodness! We’re going over! So, that was a treat.” (28)

News-Register image of the playground that was far less popular than the nearby slag dump for playing.

News-Register image of the playground that was far less popular than the nearby slag dump for playing.

The effect this dumping created was that of an apocalyptic desert landscape that proved irresistible for us kids. We played in it at every opportunity -- and always for longer than we played in the playground itself -- pretending to be on the Planet of the Apes, and taking the sand rocks home to make, well, sand – by scraping it over window screens. Why? No good reason. It was probably toxic. But I don’t recall ever being shooed out of our sand grasshopper infested desert landscape, adjacent to which was a small forest known as “the jungle.” These were days of high adventure, made possible by iron production". In a search for photographs, I decided to share this memory in the Warwood Memories Facebook Group. It soon became apparent that being a "Dump Kid" was a right of passage for North Warwood.

"We used to hike across 'Bloody Bones' (the creek behind the Presbyterian church on 22nd street that ran orange from what was apparently coal mine effluent) and hoof it over to the sand pit to play." Maureen Carrigan reported. "We carved furniture out of those blocks of sand and played softball in that field. Never knew what any of that was until well into adulthood."

"My Redbird teammates and I used to make things like rings out of the sand clumps." Paul T McIntire Jr. added. "I also made tombstones for my pets out of them, when I was a kid."

"What Warwood kid didn't have the orange stain's from bloody bones on their tube socks growing up?" Troy Leland asked.

"We were apparently all dump kids." Maureen added. "And how did we never question that our supply of toxic waste sand blocks kept getting replenished?"

I did some newspaper searches and found this, from the September 24, 1972 News-Register:

"'Down on the dump.' For several generations of youngsters growing up in the North Warwood area, that response was the one they generally gave to mother's query, 'Where are you going? [but]...Going down on the dump is now virtually impossible...There will be fewer soiled clothes for the Petrini, Panos, Swan, Pavlick, Duffy, De Santis, and Provenzano kids, happier mothers and more civic-minded fathers, says Baller [Tom Baller, head of the Wheeling Recreation Dept. at the time.]"(29)

It was rather jarring for this researcher to see his own name in print when he was only six years old, even before the Steelers had won a championship, but it was also gratifying to have my "Dump Kid" Cred established in the local press. I remain completely mystified as to how this happened.

But I digress…

Back at Centre Foundry, Cast iron was refined around the clock from “buttons” and scrap steel from blast furnaces and factories all over the Ohio Valley and Pittsburgh area. “They also used molds that finally failed," Frank explained. "They’d buy that back from the steel companies. And they’d break that up and re-melt it.” Hoisted by cranes outfitted with huge electromagnets, this iron was dropped into the vertical channels of the furnaces, a process known as “charging.” Alloys were added to adjust the chemistry and a method called “pushing” was used to break the crust on top of the molten iron to release impurities. “We had [electro] magnets there that picked up anywhere from 10,000 pounds [of scrap] to 65,000 – I’ve seen a magnet pick up. But you don’t want to be anywhere around it if for any reason the power would cut out—it let’s go. Down it comes.”(30) The scrap must be dry when placed in the furnace. “You do not put wet scrap into a furnace.” Frank cautioned. “That’s what causes explosions."

Watch video of molten iron being used to prime a furnace: part 1 and part 2; molten iron being poured into a pan: part 1, part 2, and part 3; video of spreading vermiculite on a pan that’s just been poured, which holds heat in to slow the cooling: part 1 and part 2. and video of skimming impurities into a slag pot. All videos courtesy Frank VanSyckle.

View Frank's Centre Foundry photographs.

When all is balanced, the liquid iron is poured into a ladle or “tipped.” The ladle is ten feet in circumference, holding up to 50,000 pounds of molten iron. Impurities are again skimmed off using a wooden hoe. The iron is then carefully poured into a mold with risers to allow air to escape and left to cool. “As for the void in the center of the mold, it too is a sand core," Frank elaborated. "Back in the 60's and 70's, mother's had this, similar to an ice tray, that she would fill with kool-aid flavored water to make small Popsicles. In the center was the handle that went to the bottom of each individual ‘mold.’ If you pulled out the handle of the Popsicle after it was frozen, you would have a void. We used sand cores that went all the way to the bottom of the mold. Once the iron was poured and cooled down, we would shake out all the sand from the casting and you would have a void in the middle.” (31)

Skimming a ladle.

Skimming a ladle.

The molten iron was being poured into a runner cup, which was lined with 4-inch ceramic tile that ran down inside the flask. The tile left a void so they could pour the iron down and it came in at the bottom. After cooling, with the sand, risers, and drag removed the casting was then extensively cooled and cleaned by a “chipper,” whose job it was to remove sand and various coatings that were present on a casting. In the old days, hand tools such as a hammer and a chisel were used. In modern times a pneumatic hammer, chisel, or grinding wheel. Either way, it was exhausting work. “When you’re inside chipping on those, you had to wear earplugs…" Frank said. "The pneumatic tools with a steel chisel banging on that cast iron was very loud.” (32)

“The men wearing the silver jackets were the ones who worked around the molten metal," Frank said. "You had the skimmer, who skimmed the impurities off the top of molten iron in the ladle. Also, the ladle man pouring the iron would wear the Silvers. The Melter was also wearing Silvers. Silvers were the gloves, head piece, jacket, and some even wore spats or pants.” In 1989, Centre Foundry had the honor of making a tribute to the men who wore the silvers. Created by artist Dimitrious Akis, the "Ohio Valley Steelworker Statue" was cast at Centre Foundry. Depicting a steelworker wearing silvers and pouring molten steel from a ladle, it stands near the Steubenville Public Library. The Steelworker has an iron rod with a test cup at the end, trying to get a sample. The statue was made while Frank was training to be a journeyman molder with Nick Marides. The statue was made in one take. "the statue itself -- it's beautiful..."(33)

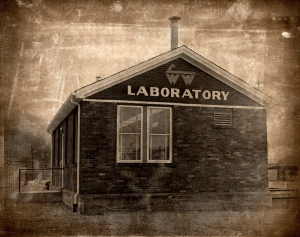

In the golden year of 1973, Centre Foundry installed its own state-of-the-art laboratory, converting an office building from the Wheeling Traction Co. era at the north end of the facility to do research for the CWW group. The three facilities each used different types of furnaces to make iron, and research into the microstructure could reveal the quality of the iron. Different types of sand and alloys could also be tested by metallurgists with results revealed in a more efficient manner than sending the work out. (34)

In the golden year of 1973, Centre Foundry installed its own state-of-the-art laboratory, converting an office building from the Wheeling Traction Co. era at the north end of the facility to do research for the CWW group. The three facilities each used different types of furnaces to make iron, and research into the microstructure could reveal the quality of the iron. Different types of sand and alloys could also be tested by metallurgists with results revealed in a more efficient manner than sending the work out. (34)

In 1979, with the Wadsworth subsidiary already closed, Dyson-Kissner-Moran Corporation bought out Centre Foundry and its remaining subsidiary, Washington Mould, ending the Young family’s 98-year ownership.

In the 1980s, Centre Foundry began an ambitious project, partnering with a British steel company to manufacture compacted graphite ingot molds. Initiated by James Bealer, the project was dropped when he passed away unexpectedly. (35)

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Centre Foundry began exporting its products to Norway, Canada, and Australia, among other places. Meanwhile, Wheeling Pittsburgh Steel upgraded to continuous casters, meaning they no longer needed Centre Foundry, which was left with only smaller, specialty steel companies as customers. (36)

Frank told us about a surprising additional function of Center Foundry: it was used by law enforcement agencies to dispose of drugs, weapons, and other contraband when a case was concluded and the evidence was no longer needed. He recalled the Ohio County and Belmont County Sheriff offices, Bethlehem Police, and the Ohio Valley Drug Task Force using the extreme heat of liquid iron for this purpose. The FBI even used it to dispose of files from the infamous Paul Hankish prosecutions. (37)

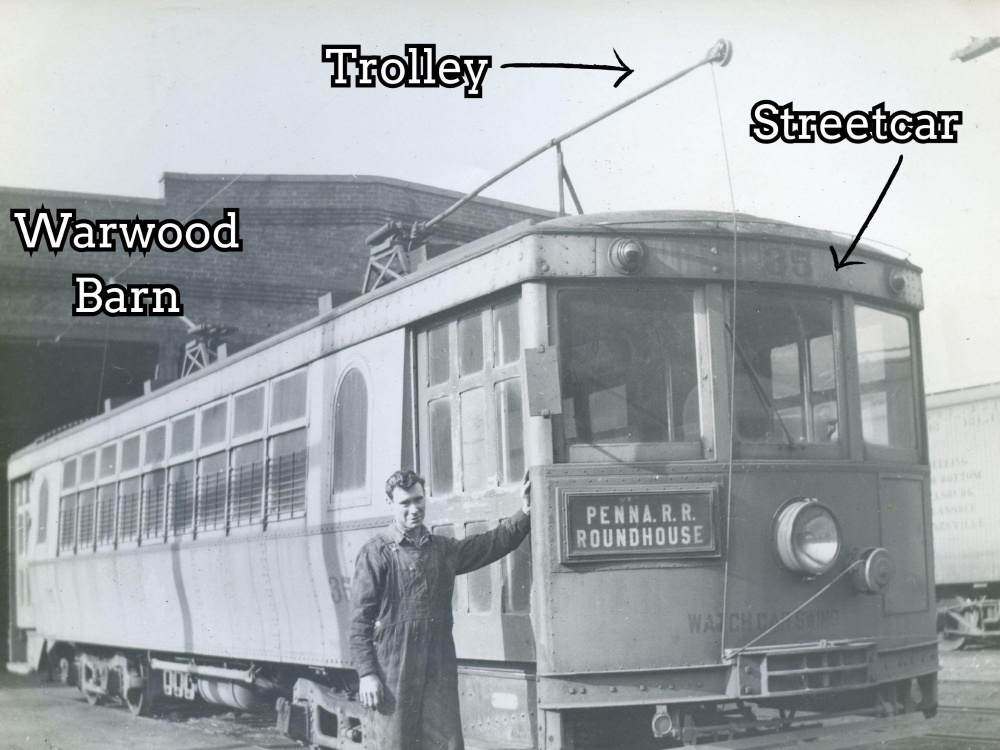

One of the stops on our tour was at what used to be (until 1949), the streetcar barn for Wheeling Traction Co. Even though it went unnoticed for all those years, there was still a sign up in the rafters on which could barely be seen the words "PULL DOWN TROLLEY." Of course, the "trolley" is actually the pole(s) on top of the streetcar connecting to the overhead electrical grid that powers the car to move along the track. So the sign was telling crew to lower the trolley before backing into the barn, which once had trenches that allowed mechanics to access the bottom of each vehicle for repairs as seen in these images from the Gwinn Transportation Collection. Amazingly, that sign had been up there collecting a thick layer of dust for 75 years, and who knows how long before that? Now it is part of the OCPL's transportation exhibit.

One of the stops on our tour was at what used to be (until 1949), the streetcar barn for Wheeling Traction Co. Even though it went unnoticed for all those years, there was still a sign up in the rafters on which could barely be seen the words "PULL DOWN TROLLEY." Of course, the "trolley" is actually the pole(s) on top of the streetcar connecting to the overhead electrical grid that powers the car to move along the track. So the sign was telling crew to lower the trolley before backing into the barn, which once had trenches that allowed mechanics to access the bottom of each vehicle for repairs as seen in these images from the Gwinn Transportation Collection. Amazingly, that sign had been up there collecting a thick layer of dust for 75 years, and who knows how long before that? Now it is part of the OCPL's transportation exhibit.

Frank watched the 1965 expansion of the north end of the plant from the porch of his grandmother’s house across the street. “The ironworkers were putting up beams for the crane rails. I’d sit on her front porch and watch those guys climb up on those things.”(38)

Union stickers still adorned workers' lockers when we visited.

Union stickers still adorned workers' lockers when we visited.

Steelworkers local president Ed Dalto and vice president Mike Funkhauser display a hard-earned safety award.

Steelworkers local president Ed Dalto and vice president Mike Funkhauser display a hard-earned safety award.

On September 24, 1952, Centre Foundry employees, after 82 years without a union to represent their interests, voted to join the United Steelworkers of America. Local 4842 was born with Stanley Wilson elected first president. When the company ceased operations on August 31, 2023, 37 union employees lost their jobs. (39)

“Bill Mudge was vice president of the company for many years," said Frank. "He was the one we dealt with in labor negotiations. He pretty much ran the plant. Very smart man.”(40)

“Yellow hats were salaried, and white hates were hourly," Frank said. "I was in the union for 25 years. I think nine of those years I was president of the union. Steelworkers. It was interesting. Had I not had the injuries I had I probably would have stayed there, but my back wouldn’t take it. Foundry work was very hard…My shoulders were shot. And I took a foreman’s position. And I just loved it. I got along with everybody. I was ex-president of the union. I knew the contract. And I think that’s one of the things the company realized, being that I was from that side…and one thing I’m proud to say is that in all the years that I was ‘in the company’ I negotiated every contract – never had a strike. Never had a strike.” (41)

Trends with steel and specialty steel had been spiraling downward in recent years. “[Our customers were] all steel companies." Frank explained. "Wheeling Steel; Wheeling-Pittsburgh; Weirton; US Steel; Standard Steel. And of course, over the years, once the steel companies started to go out of business, you had major companies like US Steel and Standard Steel. Republic went out. We used to make molds for Shenango. They’re gone. They’re all gone.”(42)

But the sudden end of Centre Foundry took employees by surprise. Many felt blindsided. On August 31, 2023, just one day after signing a contract extension with the union employees, the company announced that Centre Foundry and Machine “would be ceasing operations” because the company had been sold. The painful process of emptying the foundry of its iron, patterns, and tools began. (43)

The last pour.

The last pour.

Watch video of The Last Job Ever Poured at Centre Foundry. Typically, leftover iron was dumped in the furnace to reuse. This batch went into the hot pile because it was the end of the furnace. 09-01-2023. Courtesy Frank VanSyckle.

Longtime employee and union leader Tom Hoffman, whose own great-grandfather and uncle had also worked at the plant, told the News-Register: “I feel bad for the guys, not just myself. It’s going to be rough starting at the bottom. Wherever you go, you’re going to be the new guy.” (44)

"We thought we were doing really well," he told WTRF. "Things were going great. I mean, you know, we knew things were slow, but we had no idea they had any intention of selling it. I mean, they didn’t give any of those guys a heads up, me or any of the union guys just came in. You know, one day we signed a contract extension, the next day we’re closed.”

Tom also told WTOV, “You'd never think a business that's been around since probably the 1840's, you'd lose your job, but I guess everything has to come to an end. It's sad."

Dave Zdoncyzk (far right), was saved by CPR training used by Donnie Waddle, electrician Carl Miller, and a security guard from McKeen (far left). The men got awards for saving Dave when he had a heart attack in shower. This is Frank's fondest memory.

Dave Zdoncyzk (far right), was saved by CPR training used by Donnie Waddle, electrician Carl Miller, and a security guard from McKeen (far left). The men got awards for saving Dave when he had a heart attack in shower. This is Frank's fondest memory.

Asked for his parting thoughts, Frank said the following: "I'm gonna miss the place. It's heart-wrenching to know that it's not a foundry anymore. All the patterns are gone, all the scrap is gone, the employees have moved on. The one thing I can say is...there was an individual who finished nightshift and he was in the shower room, and there was a guy in there washing his hands, and he heard a loud thud. He said he knew the guy was in the shower so he hollered in to him, he said "You OK Dave?" No answer. So he goes in and checks and the guy's dead on the floor. He immediately hollers for the guard to call 911 and he gives him CPR from the training classes we gave. The paramedics came. They all thought he was dead. The paramedics took him to the hospital, and they saved him. He had a widow-maker and they saved him. He came back, and I think he worked for a short time...It was a stroke of luck that somebody was there that had the training. The training paid off..We were given an award by the American Heart Association I believe. We gave out plaques to the ones who were there...[one of the TV stations interviewed them]...and I can remember telling them, 'You know, when you work with these guys, day in, day out, six days a week...you get to be with them more than you are with your family. So they are your family. And it would be traumatic to see someone lose their life in front of you like that when you're so close to them. Everyone stood up and did their part and the man was alive. That's the one thing about that place. Everybody had to work together, and they did, and you know, if someone was down and out, we'd all chip in to help. That's the part I'm gonna miss, I think.

I do miss. I do miss it. That's it."(45)

Don't miss the exhibit:

Special thanks to Jim Yuncke (former Controller at Centre Foundry), Tom Hoffman, Jr., Brad Kent, MarySue Szymialis, Frank VanSickle, Laura Carroll, Ellery McGregor, Johnathon Porter, Dillon Richardson, and Sandra Caldwell (McClellan Signs).

1-Though this has been reported by secondary sources like WTRF, no corroborating primary evidence has been found so far, though the idea seems likely.

2-See ad, Album 1, Centre Foundry Collection, OCPL Archives.

3-See note 1.

4-Wheeling News-Register, July 8, 1973, p. 21.

5- See, for example, AtlasObscura.com.

6-Wheeling Register, April 5, 1928.

7-Doman, D. "Centre Foundry & Machine Co., Wheeling, West Virginia, 1840-2001." Compiled 2001.

8-Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, Aug. 8, 1853.

9-Facsimile of original Articles of Incorporation, Album 1, Centre Foundry Collection, OCPL Archives.

10-Wheeling Register, April 5, 1928.

11-Ibid.

12-Doman.

13-Wheeling Register, April 5, 1928.

14-Callin's Wheeling City Directory clippings, album, Centre Foundry Collection. OCPL Archives.

15-Wheeling Register, April 5, 1928.

16-Doman.

17-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

18-Ibid.

19-Ibid.

20-Doman.

21-“Ohio Valley Made: 165 Years of Centre Foundry.” Valley Magazine. Nov. 2005, pp 16-18.

22-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

23-Ibid.

24-International Metallics Association. Mettalics.org.

25-Wheeling News-Register, Aug. 14, 1972.

26-Wheeling News-Register, July 8, 1973, p. 21.

27-Wheeling News-Register, Sept. 24, 1972.

28-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

29-Wheeling News-Register, September 24, 1972

30-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

31-Ibid.

32-Ibid.

33-Ibid.

34-Doman.

35-Doman. See also brochure, Centre Foundry Collection, OCPL Archives.

36-“Ohio Valley Made: 165 Years of Centre Foundry.” Valley Magazine. Nov. 2005, pp 16-18.

37-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

38-Ibid.

39-“Ohio Valley Made: 165 Years of Centre Foundry.” Valley Magazine. Nov. 2005, pp 16-18.

40-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

41-Ibid.

42-Ibid.

43-Wheeling Intelligencer, September 7, 2023.

44-Wheeling News-Register, Sept. 10, 2023 (*)

45-OCPL Archives interviews with Frank VanSyckle, July 24, 2024 and July 31, 2024.

© Copyright 2025 Ohio County Public Library. All Rights Reserved. Website design by TSG. Powered by SmartSite.biz.