Wheeling: Birthplace of the American Steamboat

OUR CITY HAS A NEW HISTORICAL HIGHWAY MARKER

OUR CITY HAS A NEW HISTORICAL HIGHWAY MARKER

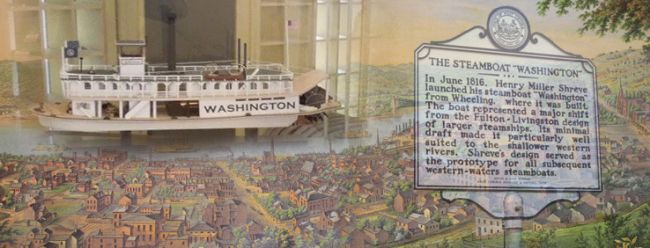

Riverboat historians consider Wheeling the “Birthplace of the American Steamboat”, and this new West Virginia Historical Highway Marker recently installed at Sixteenth and Main Streets commemorates that fact. The marker is provided by John Bowman, with support from the Wheeling National Heritage Area Corporation.

Henry Miller Shreve built the steamboat Washington on the north bank of Wheeling Creek. This site is now the parking lot south of the “WesBanco Arena”, west of Main Street along Wheeling Creek. Shreve chose this spot when he came to Wheeling, Virginia and laid the Washington’s keel September 10, 1815. Wood to build the hull and superstructure came from the timbers of Wheeling’s old Fort Randolph, U.S. Troop Garrison, which stood nearby.

The steamboat Washington was the first of its kind in many respects. She was the first steamboat with a flat-bottomed hull allowing her to skim over the water, not cut through it; the first boat with high-pressure steam engines; the first double-decker steamboat; and the first to have a ‘hogging frame’, ‘Hog Chains’, whose purpose was two-fold: to control any limberness in boat handling, and allow for flexibility at bow and stern, an advantage sailing in shallow water. She was also the first steamboat to suffer an explosion of her boilers.

Another first: while the Washington awaited its steam machinery from Brownsville, Pennsylvania, Shreve had his boat carpenters build a covered bridge, Wheeling’s first bridge, likely contracted and financed by Peter Yarnall , Noah Linsly and Noah Zane across Wheeling Creek to the south bank, which served Wheeling until it was carried away by an ice gorge in the winter of 1832. In 1832-33, the first “stone bridge” over the creek was constructed. Wheeling’s present Main Street Bridge begun in 1891, replaced the 1833 stone bridge.

The Washington was launched and set sail for New Orleans June 3, 1816. Her sixth day out, near Marietta, Ohio, the end of one of her engine’s cylinder was blown off. A column of scalding water was thrown among the crowd, inflicting injuries on nearly all of the boat’s crew and passengers. Seven were killed outright and seven were wounded by inhaling the scalding steam. Several of the wounded died a short time afterwards.

The Washington, soon repaired and newly provisioned, got underway September 9th. She arrived at Louisville on September 20th and reached New Orleans on October 7, 1816. Shreve made two successful trips to Louisville and back to New Orleans and on her third, she made Louisville in 24 days. This voyage, historians claim, was the beginning of steam-powered inland river navigation and convinced the public that steamboats were the future.

Garnett Eskew writes, “When Shreve’s steamboat took shape on the ways at Wheeling, Virginia, the whole of the surrounding river country came to ridicule her and her builder. For the craft, which Shreve built, violated, in her make-up, all the accepted principles of shipbuilding. Shreve flung to the winds all precedent.”

Shreve’s Washington had proved she could successfully bring a full cargo up-stream under her own power and she was the first. The Washington would be the prototype of all future Western River steamboats, and Wheeling was thereafter known as the “Birthplace of the American Steamboat.”

Want to keep up with all the latest Library news and events?

Want to keep up with all the latest Library news and events?